There are moments in the life of a journalist in which he needs to abandon neutrality and objectivity just to embrace his subjective and personal perspective, saying “I” instead on “us” or “one”. For me, this moment came last Friday when I finally stood in front of “the one” – the car that I have adored since childhood, that has inspired me to follow my fascination for cars, that fuelled my passion of 1970s Italian design until this day. The flat yellow Lamborghini Countach LP 500 had just been unloaded in the driveway of the Grand Hotel Villa d’Este on the shores of Lake Como, scissor doors raised into the sky, and I had a strong sensation of déjà-vu – even though I had certainly not seen this car before: After all, it had been destroyed during crash testing on 21 March 1974 at the MIRA test track in the UK, more than four years before I was born.

Last days before the show

Standing next to me was Swiss car collector extraordinaire, Albert Spiess. He had commissioned the project in late 2017 – and was now seeing the result of this unlikely endeavour for the very first time. Then the engine was started, the devout silence was broken, the car came to life with a roar. I felt time-warped back to the final days before the Geneva Motor Show in March 1971 when designer Marcello Gandini and everyone involved in the development of this all-new supercar to replace the Miura were doing their last touches. After all, the team at Bertone had only received the engine and chassis from Lamborghini in the first days of January 1971, leaving them less than eight weeks to apply their design.

The workflow was very different back then – fashionable words like ‘rapid prototyping’ or ‘agile design’ did not yet exist, but designers and engineers experimented and improvised on a daily basis, remixing existing shapes, engines, and transmissions to create something new. In fact, Marcello Gandini had not come up with the wedge shape and scissor doors – which were bound to become the archetype of the Lamborghini until this day – on a blank sheet of paper. It was rather derived from Bertone’s 1968 Alfa Romeo Carabo, a concept car too wild for the Milanese car marker to consider for serial production. Lamborghini, on the other hand, had introduced a car too tame for their clientele with the Jarama and was now looking for something that offered a little more drama! The young brand’s ambitious engineers Stanzani and Dallara were already pushing for something more extreme on the engine side – and with Gandini they had found their perfect match.

CSI Sant’Agata

The saga of the Countach has been told countless times, but the details of the prototype development were always a bit blurry. So, while the team at Polo Storico usually brings back well-documented sports cars like the Miura and Espada to their former glory, their work on the LP 500 project rather resembled a criminal investigation. “We started from scratch and with extensive research,” explains Giuliano Cassataro, Head of Service and Polo Storico, as we speak during Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este. They went through archives, analysed technical drawings, meeting reports, and photographs and spoke to people who were working on the project at Lamborghini and Bertone in 1970 and 1971. “The collection of documents was crucial. There had been so much attention paid to all the details of the car, to their overall consistency and to the technical specifications.”

It soon became clear that the LP 500 prototype had been completely handmade and very different from the later production car, the Lamborghini LP 400 that was introduced in 1973. So to better understand and reenact the development process, Stefano Castricini and his colleagues had to embark on an imaginary trip back in time, relive the experience and even recreate the tools and methods needed to build the very first Countach. While the volumes of the car were defined in 3D using scans of the very first LP400, the actual metal sheets were beaten by the “battilastra” on custom-made moulds – just like it had been done half a century ago.

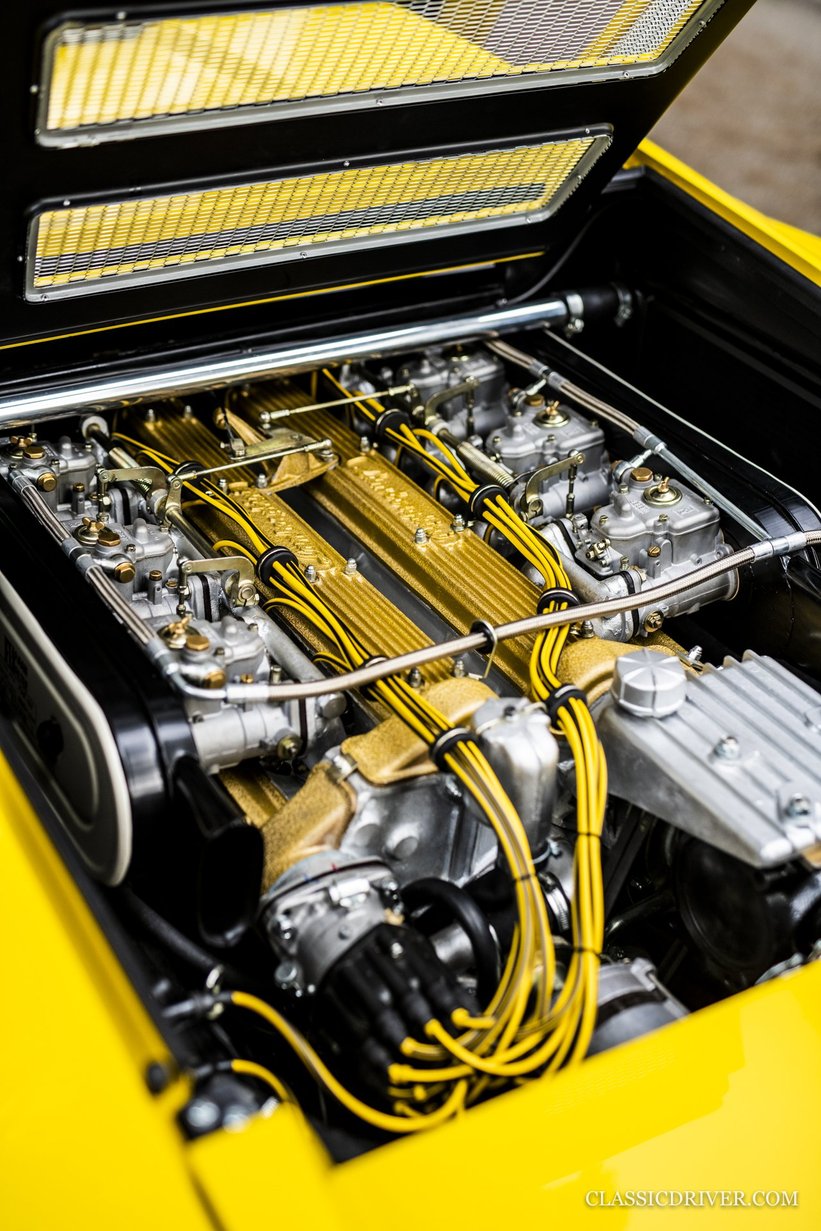

The research soon showed that many technical parts and the engine were either ‘borrowed’ from the production line in Sant’Agata or customised. “We analysed a lot of material and came to the conclusion that the engine was a normal 4-litre, 2-valves V12 like the one in the Espada or Islero with the lower area of the engine customised and reinforced”, says Giuliano Cassataro. “The name LP 500 that hinted at a 5-litre-engine rather expressed a desire, not yet a reality.” After experiments with bigger volume engines failed in period, expectations were reduced to four litres for the LP 400. Also, the chassis structure of the LP 500 was a wild mix of welded panels in the front and tubes in the rear, while the later LP 400 was upgraded to a stiff tubular chassis that was clearly an evolution. In fact, the prototype was continuously modified in terms of design and functionality after the Geneva Motor Show in 1971, learning from mistakes and paving the way for the production model.

From purism to functionality

The team at Lamborghini’s restoration department decided to recreate the prototype just like it had looked during the show – and to deliberately recreate some of the initial flaws along the way. “The air intakes weren’t functional, the degree in which the air enters the engine bay had been calculated wrong – it simply was a mistake”, explains Stefano Castricini from Lamborghini’s restoration department Polo Storico as he walks me around the car. “We now see with our own eyes how fast the water temperature is raising up and why the car needed a different solution. So for the LP 400, the cooling system got bigger and the car received its periscope air intakes.” It was one of many small steps that sacrificed the clean and sleek shape of Marcello Gandini’s original design for the sake of functionality, performance and aerodynamics until Countach production ceased in 1990.

And there are more differences between the prototype and the first production car that needed consideration. The pop-up headlights were non-functional in the show car, so the ones in the recreation cannot be moved as well. Also the rear lights consisted of one red plate that hid the indicator and brake lights. The grille is different and the front bonnet hinges in the back. Another eyecatcher are the big and chunky Pirelli Cinturato CN12 tyres. Produced as prototypes in period, they had to be recreated and homologated by Pirelli just for the LP 500 project. Opening the trademark scissor doors, we are looking at a completely customised cockpit. The square-patterned showcar seats can only be found in one other car – the very first production LP 400 production car, chassis 001, that is on display at the Lamborghini Museum.

'Vorrei, ma non posso'

The most interesting feature is the failure detecting system: Positioned on the left of the steering wheel, the iPad-style screen showcased a backlit blueprint of the car that promised to display any technical error. But electronics in the early 1970s were not that advanced. In reality, the showcar’s futuristic system was just a picture that could be illuminated by pressing a button. Same goes for the cruise control switch on the speedometer for manually setting a speed limit. “In Italy we say: Vorrei, ma non posso – I want but it can’t”, laughs Stefano Castricini. “It was a nice dream.” When Bob Wallace later tested the car, the system was already gone. When it finally came to choosing the color, the PPG archives proved to be crucial, making it possible to identify, after careful analysis, the composition for producing the yellow colour matching the original. It carries the almost poetic name “Giallo Fly Speciale”.

I want to know from Stefano Castricini, who basically spent the last two years in the early 1970s, what he learned about the workflow and production methods of his predecessors. “In that time, and especially on the prototypes, decisions were made very spontaneously: Shall we do it? Yes, ok – done! No requests, no bureaucracy, mainly because they had no time.” After all, they had to build the whole car in two month – while the recreation took more than 25,000 hours. So in terms of build quality and material, the new Lamborghini Countach LP 500 is better than the original one. “We built the car as faithful as possible to the original one”, says Stefano Castricini “But we don’t want to compare. It is a tribute in which we wanted to invest 110 percent of the capabilities at Automobili Lamborghini and show the world what is possible.” Looking at the yellow thunderbolt parked in front of Villa d’Este and considering its impact on car design and automotive history, we couldn’t think of a better way to pay homage to one of the greatest cars ever built. Or shall we just say ‘the one’?

Photos: Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2021