Housed in an early 20th Century factory formerly home to the Beaulieu camera company, the Espace Automobiles Matra in Romorantin-Lanthenay is a secret shrine to a great Gallic carmaker that, tragically, no longer exists. It was founded by the mayor of Romorantin in 2003 and comprises 70 of the marque’s cars in addition to a raft of engines, presented with the same reverence as historical artefacts.

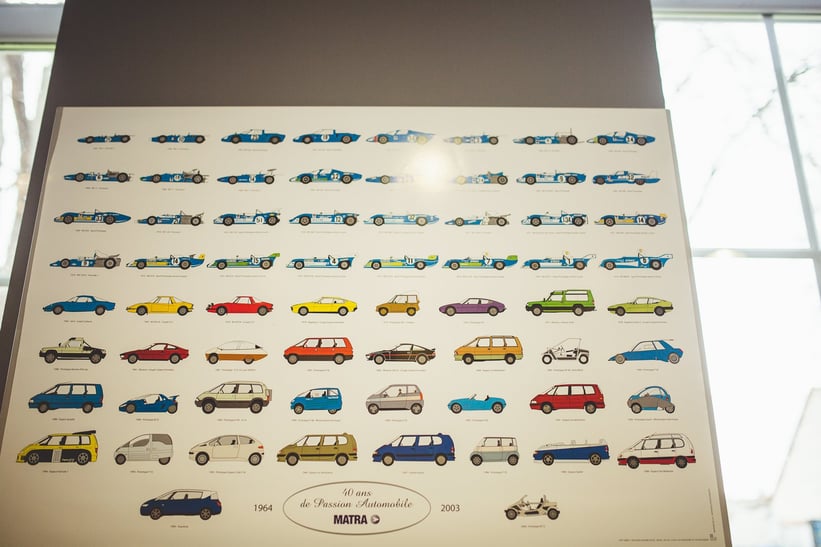

Matra will mean different things to different people: the humble Renault Espace, the quirky three-seat Bagheera, François Cevert’s ice-cool demeanour, or, most likely, the sultry, shrieking banshees that strafed the Mulsanne straight so effectively in the early 1970s.

Originally a specialist in aeronautics and weaponry, Matra was thrust onto the motorsport map in the 1960s by engineer-turned-exec Jean-Luc Lagardère, who saw competition as a means of shifting more of the road cars he was planning to build. Restoring national pride on the racetracks of the world was a bonus by-product, but one that pricked the ears and, ultimately, sapped the wallet of the French government.

‘Formula 3 to learn, Formula 2 to harden, and Formula 1 to win’ – Lagardère’s plan was clear and his execution of it absolute. Utilising Matra’s aeronautic expertise to build brilliant chassis’ and, at first, employing Ford power, Matra won the Formula 1 driver’s and constructor’s World Championship in 1969 with Jackie Stewart.

It was the celestial three-litre V12 that became the jewel in Matra’s crown. Its sonorous shriek, which is generously piped through the museum, cost many a driver their hearing. But even they would say it was worthwhile – Matra’s curvaceous open sports cars, finally with in-house engines, knocked Porsche of its perch and won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1972, 1973, and 1974.

And because Matra understandably mollycoddled a band of French drivers, such as Jean-Pierre Beltoise, Gérard Larrousse, and Henri Pescarolo, the success rendered them and the entire team certified national heroes. A French équipe hadn’t won at La Sarthe since 1950, after all.

Just how a company with no prior motorsport experience racked up 124 race wins, both Formula 1 and sports car constructor’s titles, and three consecutive Le Mans victories in just 10 years is extraordinary and telling of the marque’s unrelenting determination and ability to innovate. Suffice to say, the dramatic evolution of Matra’s single-seaters and sports-racing cars is beautifully shown at the museum.

Though Matra’s production cars were never a commercial success, despite the company’s tie-up with Chrysler-owned Simca, they did capture the public’s imagination with their eccentricity and breadth of ability. There was the Djet, a remnant of René Bonnet’s company, which Matra superseded; the M530, named after the company’s R530 surface-to-air missile; the striking Bagheera with its unusual three-abreast seating arrangement; and the Rancho, arguably the world’s first ‘crossover’ SUV. In its press material, the latter was described as ‘a very noticeable car at a rather un-noticeable price’.

There are intriguing examples of each exhibited at the museum, in addition to a generous helping of whacky concept cars and prototypes including two Espaces (the people-carrier Matra built some 800,000 of for Renault): the futuristic Sbarro-designed Espider and the Espace F1. The latter is fitted with the V10 engine from the 1993 world championship-winning Williams Renault Formula 1 car and is, for want of a better word, absurd.

During our visit to the enchanting museum, we met its director Bruno Lorgeoux, who’s made it his mission to safeguard Matra’s legacy and ensure the great French marque is not lost to oblivion. And rightfully so – anyone who’s had the pleasure of seeing and hearing a V12-powered Matra in action, be it in the period or at a recent historic meeting, will have been spellbound. In its heyday, the company employed 3,000 people in Romorantin. When it folded in 2003 following the failure of the Renault Avantime, there were just 150.

It’s a tragic tale of an almighty fall from grace. We should all be thankful that Matra’s missiles homed in on the racetrack, for if Lagardère had not orchestrated that decision, we would have been denied some of the greatest cars to have ever seen the light of day, all of which flew the French flag with an inimitably nonchalant Gitanes-fueled flair. The Espace Automobiles Matra serves as a timely reminder of that – we strongly recommend a visit.

Photos: Mathieu Bonnevie for Classic Driver © 2018