The archive is the memory of the Porsche company. Has Porsche actually been consistently collecting and archiving things since the early days?

The history of the archive begins in the 1930s. That was when technical documents and drawings were first collected. The original production plant, Werk 1, already had its own archive, but it was hit by a bomb during the Second World War . This is why we only have a few drawings and documents from the pre-war period.

After the war, Porsche first moved to Gmünd in Austria, then back to Stuttgart. Not ideal for an archive. What happened next?

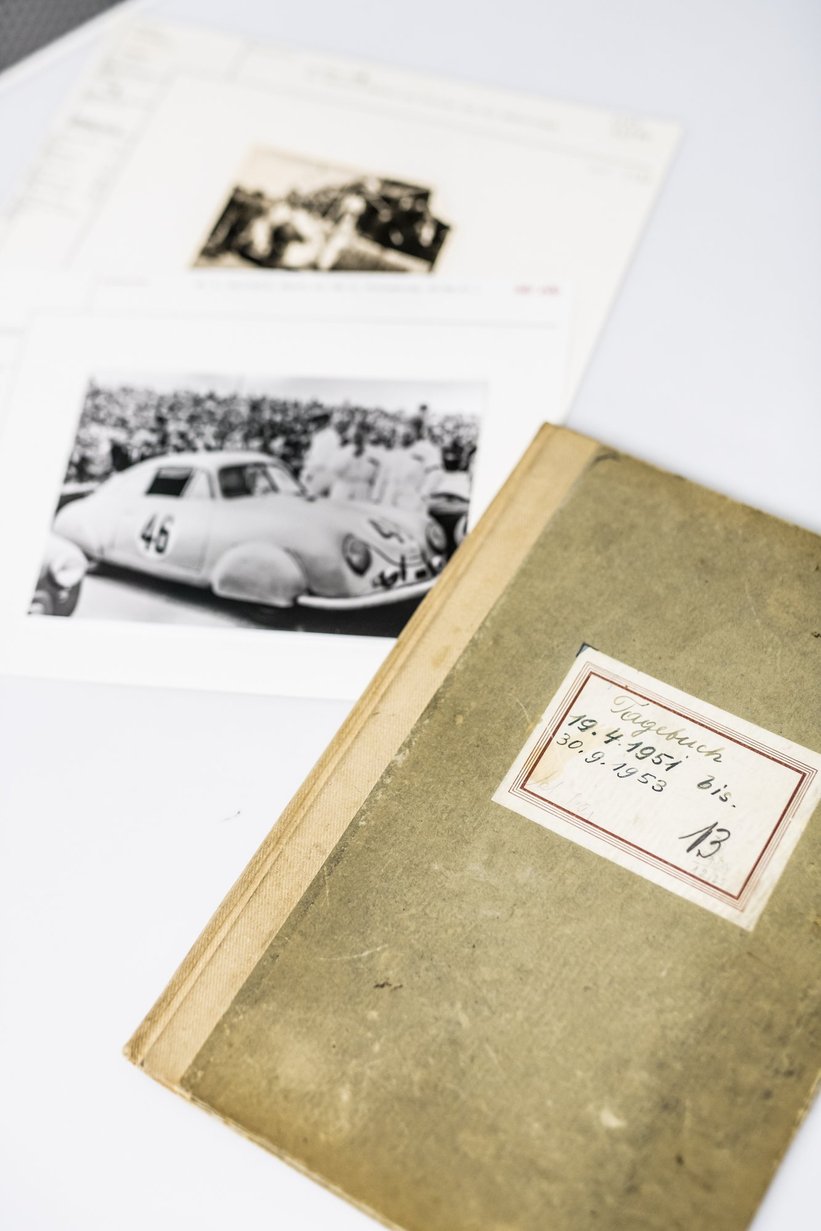

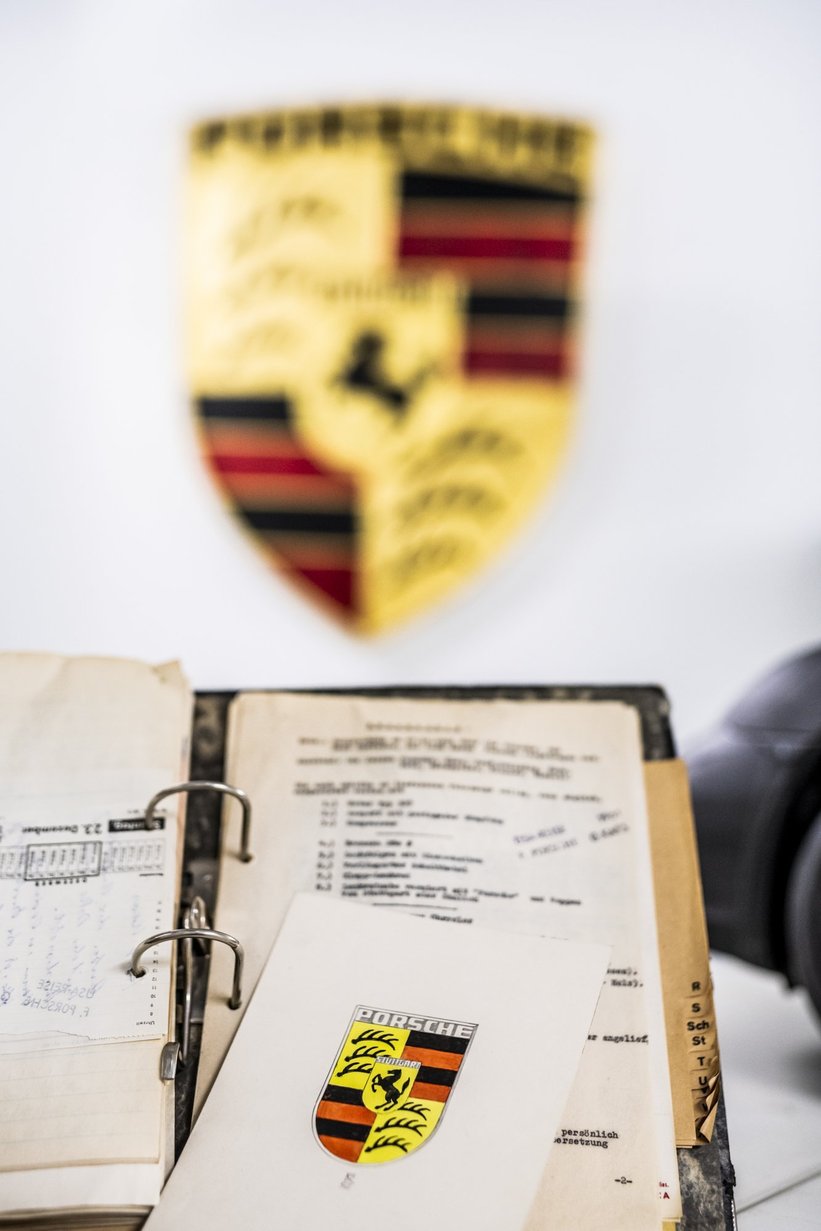

A lot was lost due to the various moves. But Ferdinand Porsche's nephew Ghislaine Kaes, who saw himself as a private secretary and historian, started documenting the company's history at that time – he also contributed significantly to the personality cult surrounding Ferdinand Porsche. The second important person in the history of the archive was the engineer Karl Rabe. He was Ferdinand Porsche's first employee. He must never have slept, because he developed and documented an incredible amount. Since the 1950s, the archive has received all photos and press releases from public relations, and contact with the racing department was also close. In the 1980s, it was finally decided to set up a comprehensive, systematic Porsche archive under the direction of Klaus Parr. The team then grew continuously and around 2008 Dieter Landenberger took over the archive. We then moved from Werk 1 to the other side of the street, to Werk 3, and finally to the new Porsche Museum. I have been managing the Porsche Archive since 2008. Since December, we have also been responsible for Porsche’s vehicle collection.

Is Porsche collecting everything?

Well, a good archive is characterized by the fact that you don't just put things away, but can also find them again. That's what distinguishes us from a collector. That doesn't mean, by the way, that as an archivist you always find everything again. (laughs)

What does the everyday life of a Porsche archivist look like? What kind of requests do you receive? And can I contact you directly as a Porsche owner?

First of all, we support the Porsche Museum in the conception and research of the exhibitions. Recently we also became responsible for the vehicle collection. We also work with journalists and customers from all over the world. We receive around 6,000 inquiries a year. What color was my car originally? How many cars were there in exactly this color? However, only 13 permanent employees work in the archive and the vehicle collection – we do not have the capacity to process all these requests. If you have any questions about customer vehicles, our colleagues at Porsche Classic will be happy to help. There you can also get a technical certificate with historical information about the car. We only prepare reports on whether a car is really genuine for the company's own vehicle collection.

Let’s talk numbers – how big is the Porsche archive?

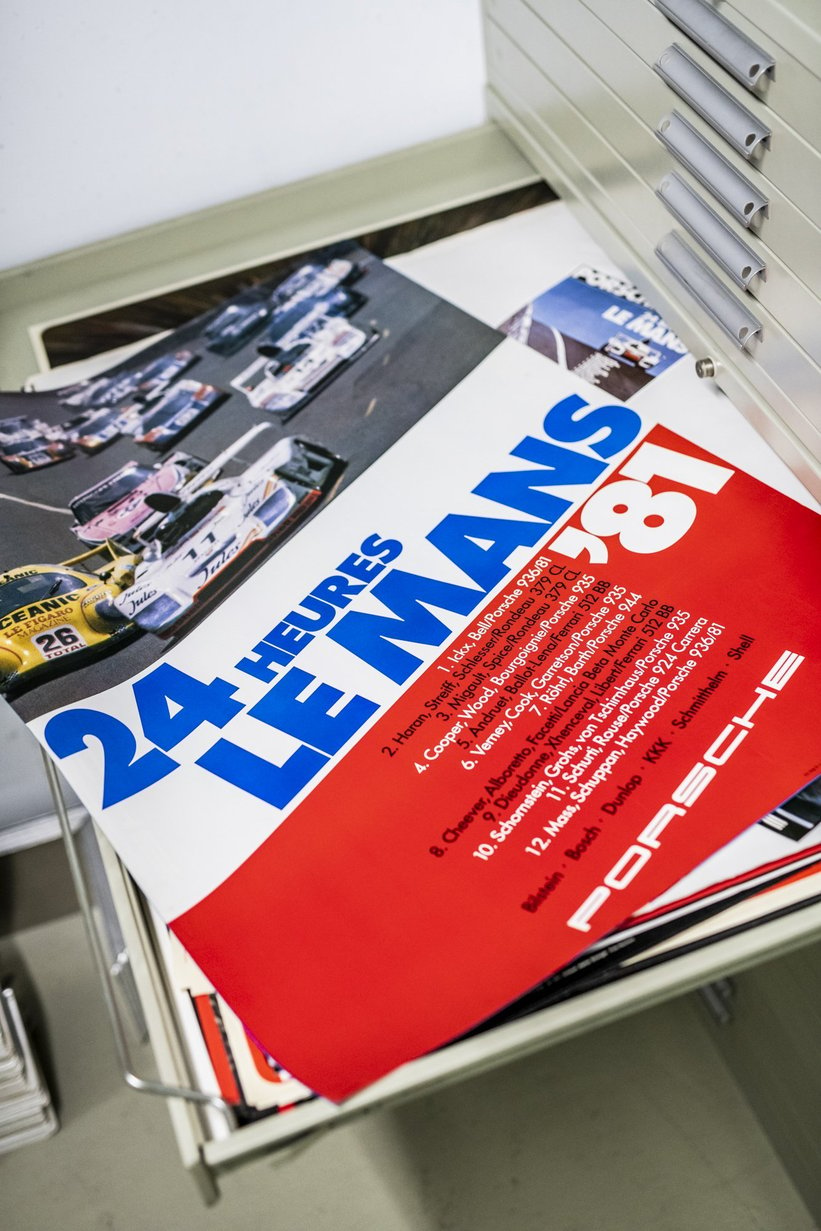

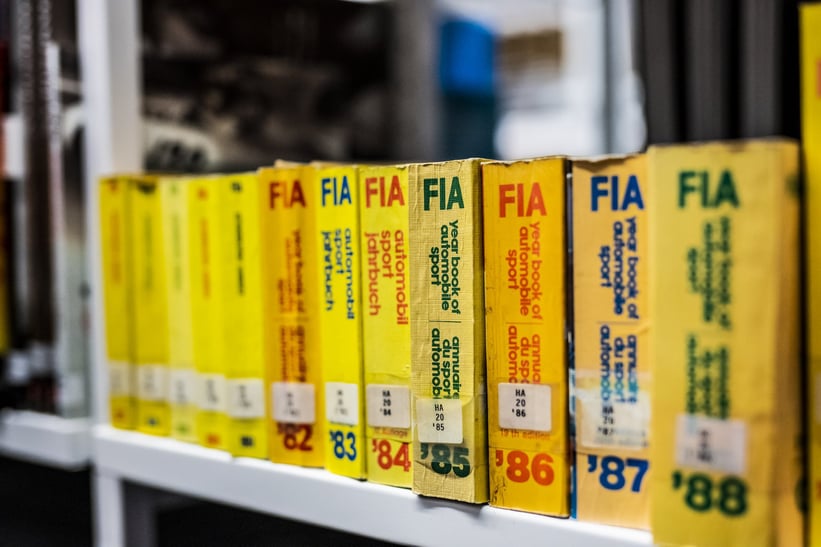

We have a total of around 1,000 square meters of archive space, three and a half kilometers of files and around five million images – digital and analogue – on slides, prints, glass plates and negatives. We have around 4,500 books and almost 3,000 hours of film. Thousands of advertisements, posters and placards. And we have 25,000 to 35,000 objects. This also includes larger objects such as one-to-four models. Everything that has four wheels and was built on a 1:1 scale is part of the vehicle collection. This also applies to technical objects such as cutaway engines or spare parts. And then there is a warehouse for design studies and numerous other sub-archives. We are trying to centralize everything more and more.

For the archive, where does the Porsche chronology begin and where does it end?

Our spectrum begins with the birth of Ferdinand Porsche in 1875 – the oldest object is a faded family photo from the 1880s – and ends practically the day after tomorrow. For example, when we provide historical support for the development of a new "Heritage Design Edition" of a current model. When we cite our own history, ideally we do so correctly.

The archive practically priceless – and its value to the Porsche brand is incalculable. How do you protect such a treasure?

The most important objects are stored in the archive rooms in the museum, where we have two rooms protected by argon fire extinguishers. This means that in the event of a fire, no damage can be caused by extinguishing water. The rooms also have a constant temperature of around 18 degrees and a certain humidity. It must not be too humid, so that it doesn't grow mold. It must not be too dry, so that things don't become brittle and crumble. Our job is to preserve things and information for future generations. The company's memory should still be complete in 200 or 300 years.

We leave Frank Jung's office and enter the first room of the archive. Files run through endless rows of shelves. Here you can find historical sales catalogues, colour cards, and the famous Kardex cards, on which every Porsche built between 1950 and 1969 is recorded. These are followed by the even more extensive production files. In them you can see exactly which car with a certain chassis number was delivered with which engine and which specifications.

Porsche's racing history is also documented in great detail – in addition to development files on legendary racing cars such as the 904 Carrera GTS or 917, you can find information on the important races here. What starting number did the first Porsche racing car start with in Le Mans in 1951? In which hotel did the team stay overnight at Rossfeld to start in the Berchtesgaden hill climb? You can find out almost everything here. A few rows further on there are drawings and drafts that show the design process of the Porsche 911. Shelves as high as the walls are filled with wind tunnel models, scale studies of concept cars that were never built, and wooden models. Historical, original racing posters hang on the walls. Porsche fans will be left breathless here.

Is there such a thing as a holy grail among Porsche's precious items? Which object in the archive has the greatest sentimental value for the company?

There are a whole series of iconic things, such as the first drawing of the Porsche crest. It was drawn by Franz Xaver Reimspiess, he also designed the Volkswagen logo. When a customer picks up his hundredth Porsche and I hand him this drawing during a private tour of the archive, he will almost certainly start to tremble.

Is there an object that is particularly dear to you personally?

Yes, and that is connected to my personal history. I used to work for the Recaro seat company, which emerged from the Stuttgart bodyworks Reutter. And this Mr. Reutter was my great-grandfather. Reutter was based opposite here in a brick building, where most of the Porsche 356 bodies were built. However, a business relationship between the Reutter bodyworks and the Porsche design office had existed since 1931. And we have a whole lot of documents about this collaboration in the archives here. For example, there is a contract that my grandmother signed. Of course, these things have a special place in my heart.

Would it actually be conceivable to digitize the entire archive and thus secure it?

We are constantly digitizing things. But a digital archive is not timeless. If a one or a zero breaks, that's it. The same goes for when an operating system or a data storage device no longer exists. A few years ago, DVDs were considered an important storage medium. But who has a DVD player these days? Still, I can just hold a slide up to the light and see what's on it. The most permanent thing is usually the original.

Given the incredible amount of material that Porsche generates every day, how is it decided what is archived and what is not?

Of course, we are confronted with the question every day: what do we keep and what do we not? Making these decisions is one of the most important tasks in the archive – and one of the most difficult. There is a company policy that dictates what we want to archive for the future. If we had to reduce the entire archive to the most important documents, they would be the board minutes. They reflect the highest decision-making level of the company. We have archived them in full since the 1950s.

Do employees sometimes contact you with items they have found?

In the past, many things have ended up in the homes of employees or their descendants and then find their way back to the archives, where they belong. But we ourselves also find amazing things every now and then: during the renovation of Werk 1, we actually found an old steamer trunk from 1936 that Ferdinand Porsche used to travel back to Germany from the USA on the MS Bremen. We could hardly believe it.

Historiography is not a static science – our image of the past is constantly changing due to new discoveries and insights. Does this also apply to Porsche history?

In fact, that's exactly how it is. Anniversaries often provide a reason to take another close look at a model or era. At the last anniversary of the Porsche 911, we discovered that a prototype that we had previously called the 754 was actually called the 695. This was a prime example of how complicated the design development from the 356 to the 911 actually was – and how many construction and design concepts were discarded in the process. Of course, a journalist would like to be able to explain the history of the 911 in simple terms. Our job is to do the groundwork for this so that the reduction in complexity is based on the right information.

So the history of Porsche is not only a great success story, but also a story of experiments, setbacks and failures?

If we only told people what was going well, we wouldn't be credible. For a technically innovative company, it's natural to try out new ideas – and of course things go wrong. I test something, it either works or it doesn't. That's called evolution. There 's a quote from Oliver Blume: "It is only because Porsche is always changing that Porsche has always remained Porsche." Looking back, it is only through innovation that we can at some point achieve tradition. Innovation and tradition are not opposites at Porsche, one depends on the other.

And the crucial question at the end: why is a modern car brand's own history so relevant? Will such an expensive archive help me sell more cars in China?

Our history makes us special. And it explains the continuity of our products, our philosophy, our DNA, but also our innovations. Porsche is now building electric cars – just as Ferdinand Porsche did with the Lohner-Porsche around 1900. And in China, people are very aware of their own cultural history, which goes back thousands of years. Porsche has only existed as a brand since 1948. But if you can tell people where you come from, it is easier to meet on equal terms. History informs, fascinates, motivates and differentiates. Especially in times when emotional factors are becoming more important, our work can help in all areas of the company. We therefore see ourselves not only as direct communicators, but also as enablers for almost all departments at Porsche.

Photos: Rémi Dargegen