Among the world’s foremost vintage motorcycle experts, Paul d’Orleans is not what you’d call conventional. But his radical and lifelong approach to, and deep knowledge of, the world of motorcycles has garnered him worldwide recognition. Among other duties, he’s edited and contributed to the foremost motorcycle magazines, authored definitive works (several of which were published by our friends at Gestalten), curated fresh and revealing exhibitions, and judged at the most significant shows, including the Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este. In 2006, he started The Vintagent, a blog dedicated to sharing not only his knowledge but also the motorcycle community. And more recently, he’s curated the Custom Revolution exhibition at the Petersen Museum in Los Angeles, a breakthrough look into the ‘Alt. Custom’ world and its cultural implications, which we’ll be highlighting in a separate story in the near future. During his West Coast odyssey, Rémi Dargegen paid Paul a visit to discover, firstly, where this passion kindled and, secondly, how it snowballed.

What are your earliest automotive memories?

When I was born, I was taken home from the hospital in a blue Rambler station wagon, which was later swapped for a new 1966 Chevy Impala in gold. I have two older brothers and, when I was four or five, I remember seeing a beautiful blue and silver car and asking them what it was. “A Triumph, you dummy!” they replied — they weren’t so kind but they preceded my interest in motorbikes. My brother Don had a Honda 500 Super Sport and a Suzuki Titan. I rode on the back and he used to scare the daylights out of me by jumping over the nearby railway tracks.

Was this when your passion for motorcycles spawned?

Motorcycles were always on the table. In 1978, when I was 15, A Honda moped transported me to night classes at the local college so I could graduate from high school early. High school was miserable and the Honda allowed me to escape — the cliché of ‘freedom’ was very real and I loved the mobility. After graduating from university, a friend of mine, Jim, who owned a 1959 BMW R50, set up a printing press in my basement. He was a good anarchist and felt guilty about his materialistic obsession with motorcycles. He’d collected every issue of Classic Bike and Classic Motorcycles magazines and, in 1984, he gave them all to me. That was the end of my former life and when I was infested with the ‘virus’ — my hungry eyes burned holes in those magazines!

You were a car guy once upon a time?

Yes, I collected sports cars in the 1980s and ’90s — among others, I owned a ‘flat floor’ Jaguar E-type Roadster, a Jensen Healey Roadster, and a Saab 900 Turbo convertible.

So why did you switch to collecting classic motorcycles?

While I have a veneer of respectability, I was a total tearaway in my 20s and 30s and used every vehicle to its limits. Cars can be as fun as motorcycles, but only if you keep the pedal to the floor, drift around corners, and pass everyone to keep a clear road ahead. After my best friend had a horrific accident, I reflected on my bikes, how you can ride like a demon and kill yourself, but with cars, the chances are you’ll take someone else with you. So, I sold all my cars and doubled-down on bikes.

How did you become one of the most knowledgeable motorcycle experts in the world?

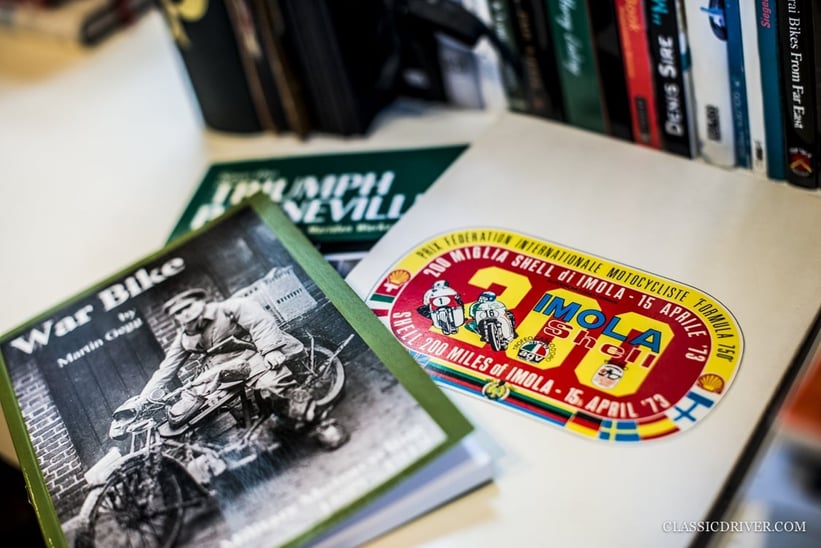

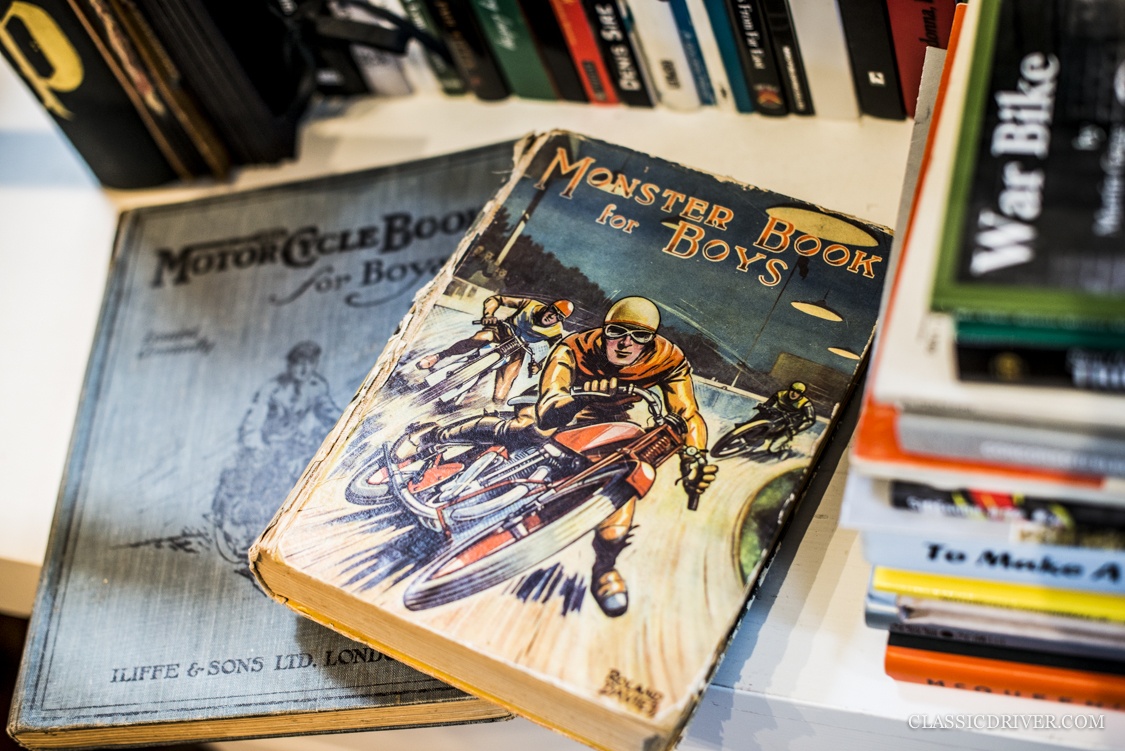

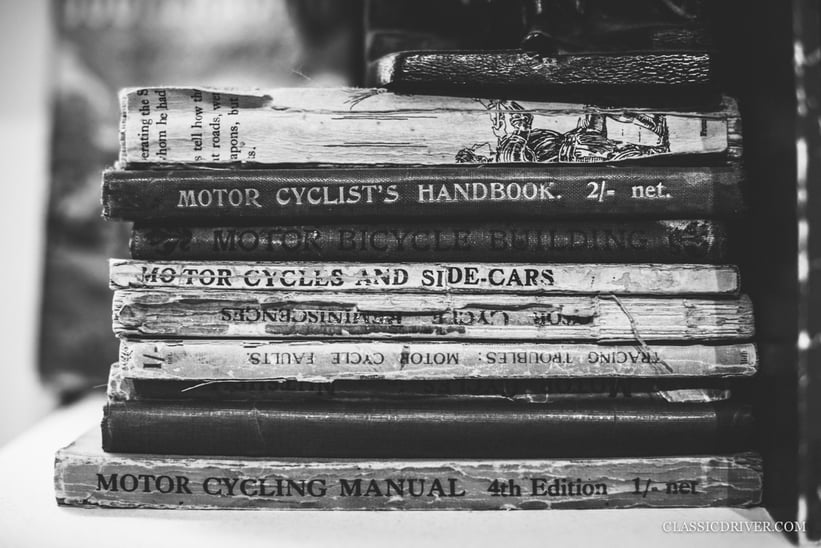

It was an obsession. In San Francisco in the 1980s, old bikes were common and cheap but there was no information on them — no internet to search for Norton Electras or Velocette KTTs. But there were books, so I spent all my money clearing every used bookshop I encountered of its motorcycle titles. In the 1990s, I stretched my search for bikes to Britain, Germany, South America, and Australia. When one is looking for Brough Superiors and other rare racing motorcycles from the 1920s and ’30s, word soon spreads and you become known as a serious person in the collecting world.

Two things changed my life in ways I couldn’t have predicted: the internet and the Legend of the Motorcycle Concours. I was a judge at the world’s most prestigious and internationally attended show for three years and met seemingly everyone from the motorcycle industry. I started The Vintagent in 2006 in response to this remarkable event, and when the blog began to gain traction, it led to a career change from interior design.

And you’re still learning something new every day?

The more I research, the more I realise how little I, or anyone for that matter, knows about motorcycle history and culture. The deeper I dig, the more I discover and the more interesting the subject becomes. Motorcycles are a hologram of the world, in that if you break them down, each part contains an image. So, when, for example, I study a photograph of the Indian Motorcycles factory in 1918, I can see the world as it was, from the architecture to the roles of the workforce and the state of the gas, oil, and rubber industries. Now you’re inside my head!

Today, what is your best source of knowledge?

There’s almost nothing on the internet about old motorcycles, despite there being thousands of websites about them. I could close my eyes, open one of the 2,000-plus books on my shelves at random, and almost guarantee that the information will not be on the web. So, if you’re looking for information, look in old books.

How does it feel to be a motorcycle judge at the Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este?

You don’t have to twist my arm to fly to Lake Como in May for a weekend filled with amazing cars, motorcycles, and people! It’s so great to meet the European collectors, and it’s an honour to be a guest at the event. Villa d’Este is the event Pebble Beach winners are dying to get into. Also, it’s led to a nice relationship with BMW, which builds motorcycles and, you know, has an incredible archive…

You’re perhaps more famous at the event for your amazing and surprising style than your motorcycle knowledge…

My mother was a fashion designer and my grandmother was an editor at Vogue, so I came by my interest in fashion quite honestly. I love design and theatre, and I’ve never minded being seen as unusual. I was a punk in the early 1980s and my first magazine gig was Maximum Rock’n’Roll, which is still extant! Before that, I worshipped Bowie. I love that the concorso is polished, but the organisers know what they’re getting when they invite me.

From our point of view in the car world, the world of classic motorcycles seems more inclusive and with far more real specialists – is that the case?

I think the motorcycle scene looks very different from the inside. From there, the car world looks very closed, totally corrupted by money and obsessed with shiny objects. Bike collectors are way ahead of car collectors in valuing originality above everything else — they’ve come to view any restoration as suspect because there are so many fakes in circulation. When something is shiny and perfect, you have no idea what’s underneath the paint or if any part is original from the factory.

Your collection of motorcycles is very impressive – how many have you owned and how do you go about choosing them?

I tried to document them all last year and I stopped at 214. The bikes in the collection have ranged from 1902 to 1992, but after a stretch in the 1980s collecting café racers, such as the BSA Gold Star and the Norton Atlas, I became more interested in racing machinery from the 1920s and ’30s. I ride everything I own, so what I’ve kept in my stable is what I like to ride in the hills north of San Francisco. They must handle beautifully, have sufficient power, and be beautiful examples of design. I have five Velocettes, including three KTT racers, a couple of Triumph Twins, and a Brough Superior 11.50 tourer. I’ve owned six Brough Superiors but I sold them in 2000, as I preferred the racers to the Tourers — I sold them far too soon! I’m a recovering motorcycle addict and do my best to keep my collection at a dozen. The struggle is real.

You have a particular affinity for Velocette – what’s so special about this brand?

I was president of the Velocette Owners’ Club for many years because I fell in love with them. It has been called the Bugatti of the motorcycle world because it was a small family firm with eccentricities in its design. The bikes were handmade and won more Grands Prix, TTs, and World Championships than such a small company should have. They’re beautiful, reliable, simple to repair, and a lot of fun to ride, even in modern traffic. I have three racing KTTs, and I’ve had my Thruxton production racer since 1989 — I bought it from the largest ‘privateer’ amphetamine manufacturer in the US after he was caught with six tonnes of the stuff. Now that’s a story waiting to be told!

Are there any motorcycles you regret selling?

Very few, and I’ve sold some world-class bikes, including a tuned 1929 Norton ES2 with an aluminium zeppelin sidecar, in which I took my daughter to school, and a 1925 Lotus Sunbeam Longstroke Sports. Both were totally original and in marvellous running condition. I sold them to buy a 1925 Zenith-Jap KTOR land-speed racer — the only supercharged bike from the 1920s still in original condition. It’s worth a million dollars today, but I sold it to buy my house in San Francisco.

What are your most thrilling riding memories?

The word thrill can mean many things. The scariest ride I ever had was on my blown Zenith-JAP at Montlhéry — every combustion was a shove in the back, there was a large crowd surrounding the short runway, and it had lousy brakes and a clutch that required gorilla strength. My most elegant riding memory was on a three-wheeled Brough Superior with a sidecar. I dubbed it the ‘Emperor of Motorcycles’, as it was automotive perfection.

In your opinion, what are the three most amazing motorcycles ever produced?

Sylvester Roper’s 1896 ‘self-propeller’, steam-powered motorcycle — the first bike that really worked, in that it was fast and ridden regularly — the 1925 Brough Superior SS100, and the 1959 Honda Super Cub.

Photos: Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2018