A fly on the wall during the golden era of Grand Prix racing, American Richard Kelley wanted to photograph F1 heroes like they were movie stars. “I’d grown up in a family who loved movies; black-and-white ’30s, ’40s and ’50s movies,” the 68-year-old tells Classic Driver on Zoom from his Florida home. “I knew exactly how I wanted to shoot Formula 1, and to do it I had to work my own way. I looked up to W. Eugene Smith and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka and those Magnum guys”, whose humanist and candid style was the gold standard for documentary photography.

Kelley was raised in Gary, Indiana, where he contested Battle of the Bands competitions against the Jackson family, soon to be Gary’s most famous residents. Spotting future talent became something he’d get good at in the motorsport world, too, as did being witness to seminal events. “I was in Chicago in 1968 for the Democratic National Convention [where a violent protest against the Vietnam War broke out]. What a time to be alive.”

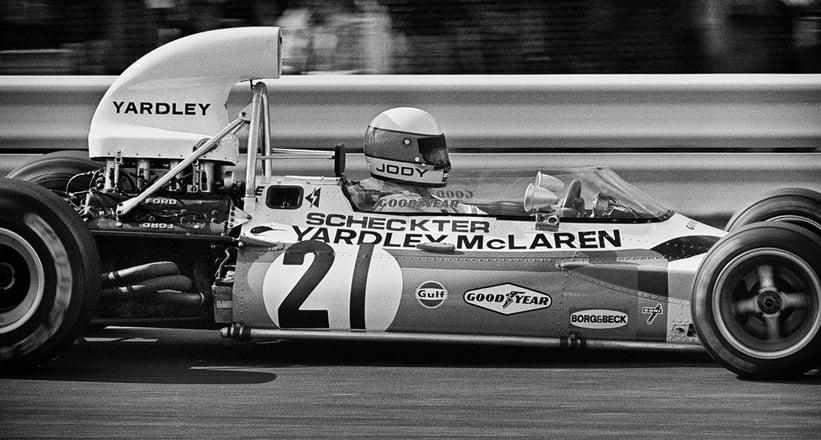

He studied photojournalism at Indiana University, got a job with the Associated Press and shot at his first Grand Prix in 1972 at Watkins Glen, aged 19 (when the age requirement was 21). He’d only picked up a camera nine months earlier. “It was intoxicating. I’d read a copy of Road & Track the year before, with a report by Rob Walker from the British Grand Prix, and it was like BOOM! I knew that’s what I wanted to cover. Once I arrived, I was in heaven. I knew this was where I was meant to be.”

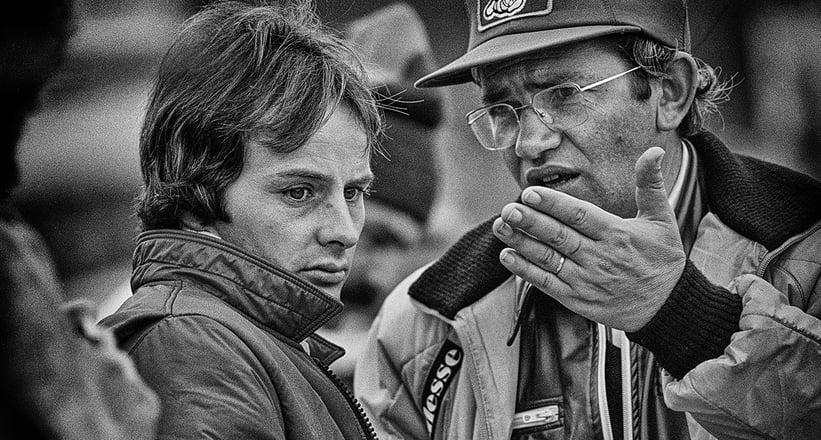

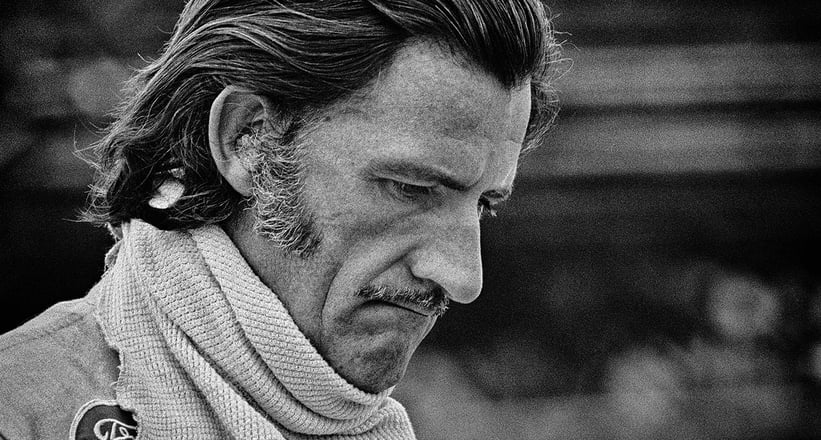

He soon developed friendships with the likes of Niki Lauda, Francois Cevert, Peter Revson, Patrick Tambay and Gilles Villeneuve. “The drivers at this time were often close friends, who’d help each other out. There was real camaraderie back then.”

Part of his modus operandi was to shoot away from other photographers. “On that first morning in Watkins Glen the head guy for AP asked me which corner I was going to be at. I told him the pitlane. ‘That’ll never get printed’, he warned. Well, I got four covers published.”

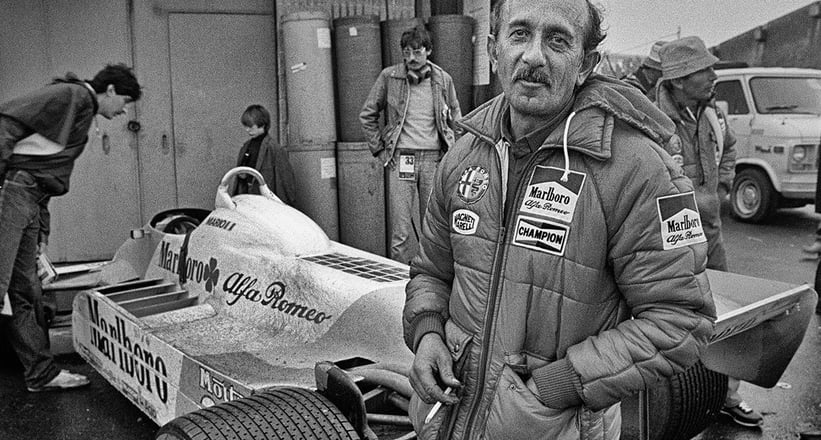

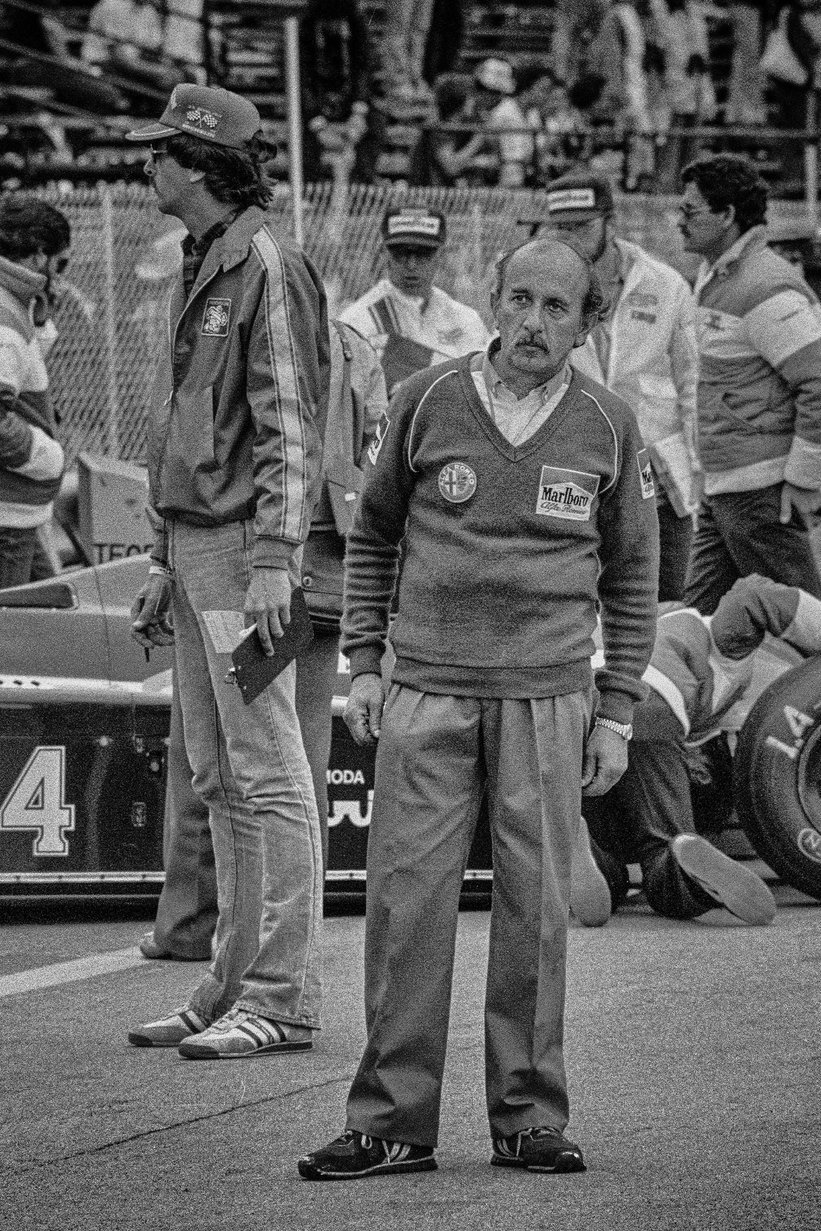

Richard went on to shoot F1 on both sides of the Atlantic for Car and Driver magazine until 1984, paying his own way to all the races. There were two regular lensmen who were initially intimidating, given their experience and talent: Paul-Henri Cahier and Rainer Schlegelmilch. “They were giants, and everything you could hope for. To start with, I wasn’t sure where I stood among the racing photographers, because I was kind of an outsider. There were guys there from Europe who had egos the size of the Empire State Building.”

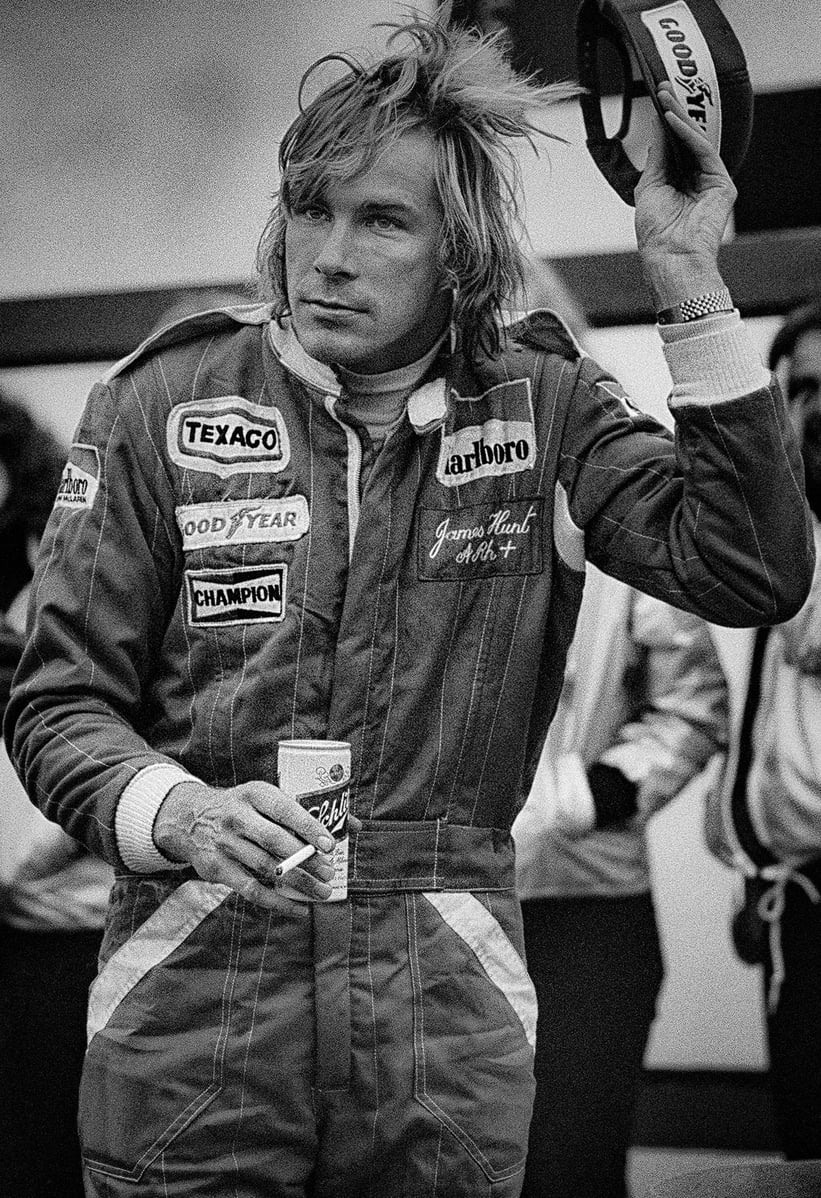

Using the technique of shooting when his rivals’ backs were turned, Kelley took one of his favourite photos of James Hunt while the other snappers were reloading film. “James was sitting on the side of his McLaren M26 with a pretty girl. I was standing with Paul-Henri and Rainer, and everyone was getting the same deadpan picture, but as they were reloading I yelled out ‘James, what time’s the party?’ And I got that perfect, unposed reaction shot”. ‘Son of a bitch’ grumbled Rainer.

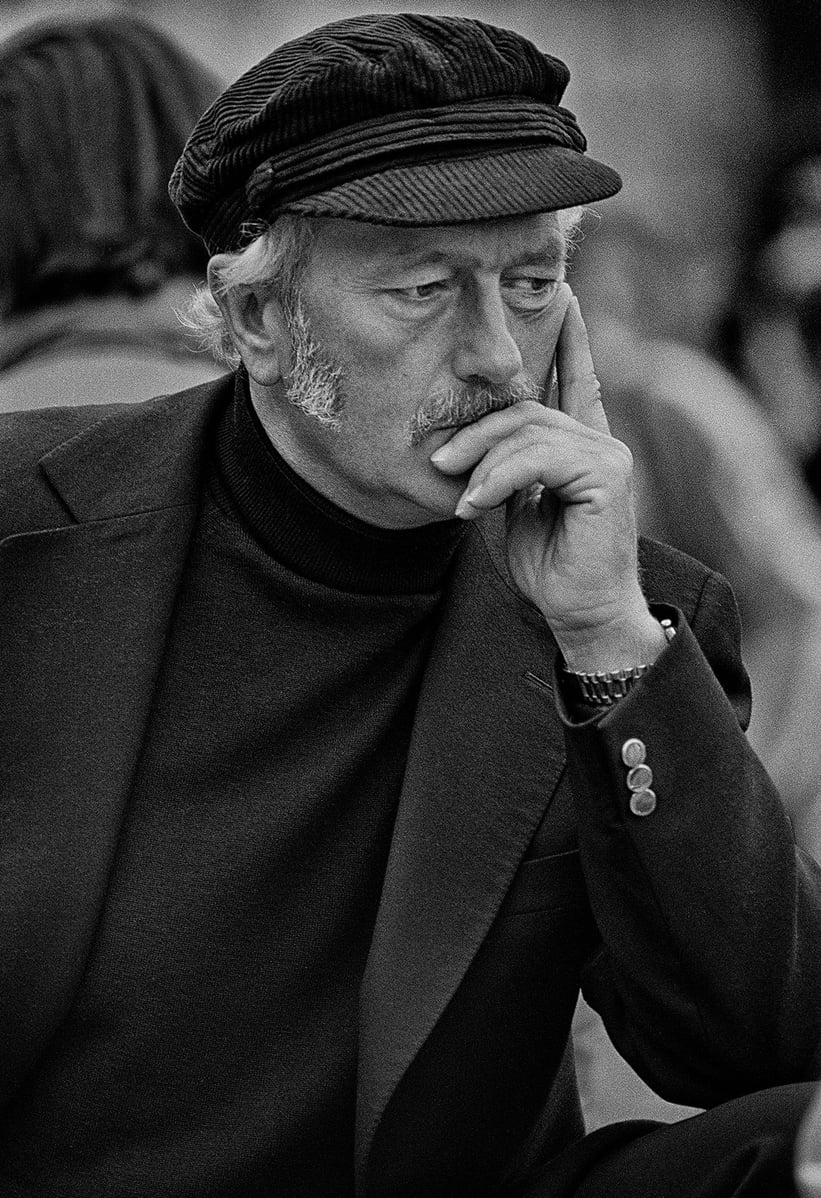

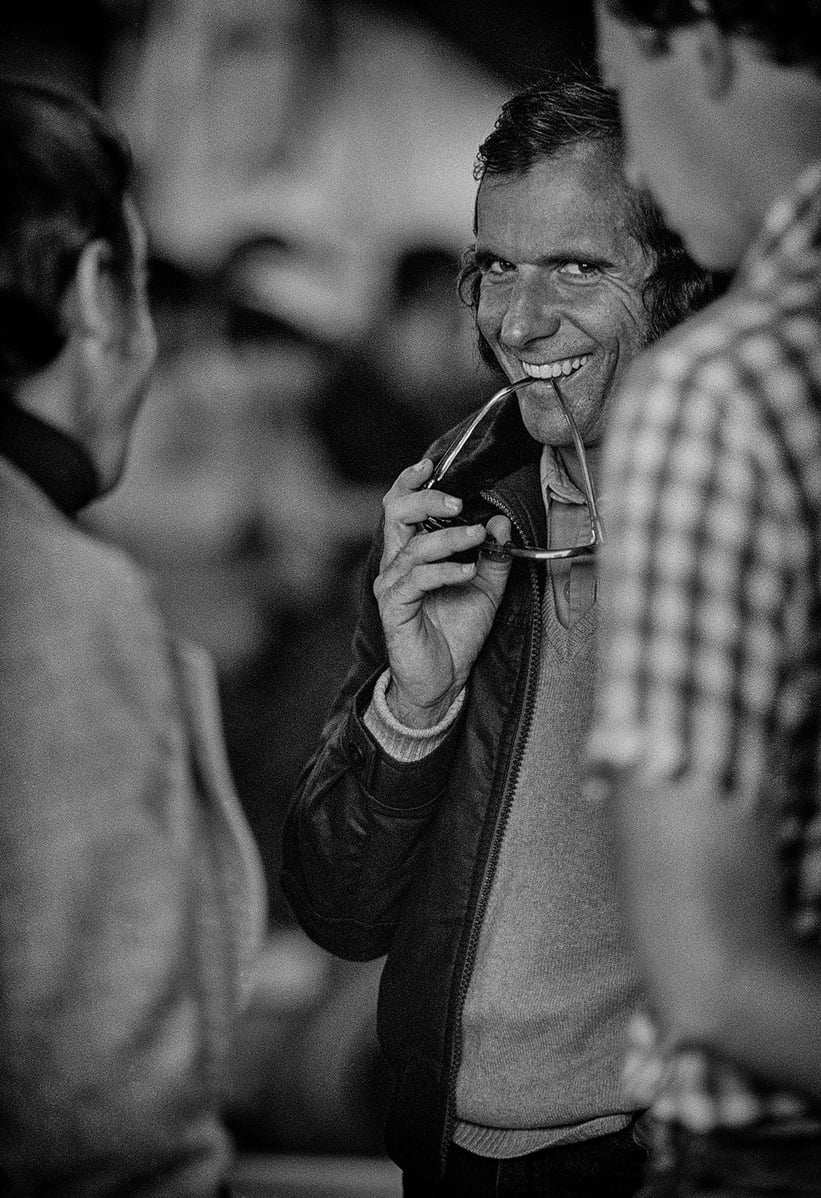

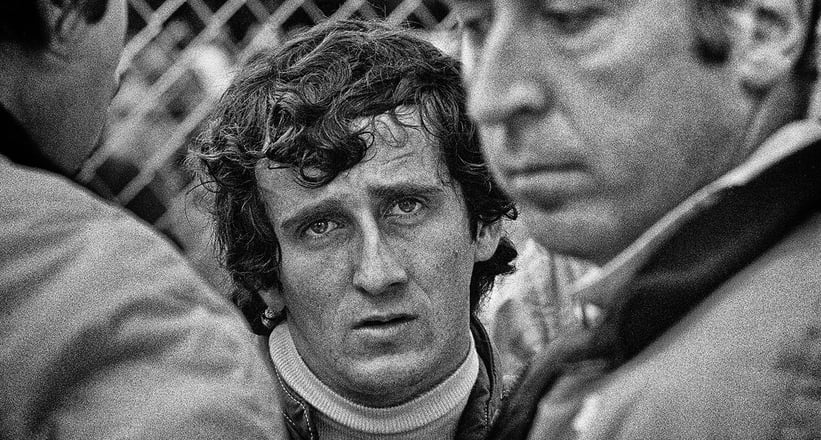

“From my point of view, the trick to these photographs is to be completely invisible. Don’t influence anything. You’re catching the faces of these guys on the limit, and it needs to feel intimate. Stylistically, I’d often position myself so someone else was slightly blocking the view, get really close and shoot through them with a 180mm lens. I’d make a large aperture with a tight focus and obey the rule of thirds. I’d let the photo come to me, let the drama of the moment make the image. It had to be cinematic, and to do that you needed to listen and anticipate when to click the shutter. I never sprayed and prayed. I only took 400 pictures, 400 of which were on the money. These were often pivotal moments in the sport that I was able to soak up, while also removing myself from these moments.”

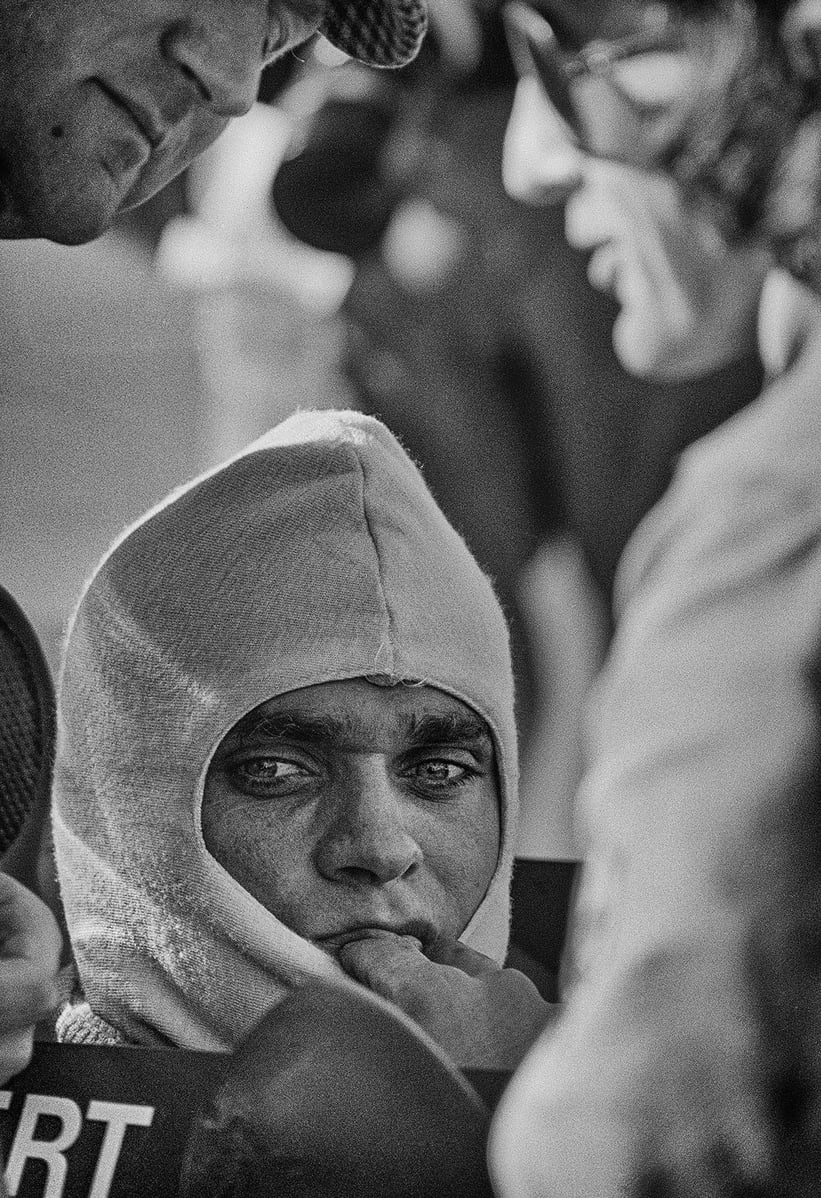

Given Kelley’s love of Hollywood, it begs the question: Who, of all the drivers he photographed, could have been a movie star? His verdict is instant. “Cevert. I have the last photograph of him alive. He had a great future; he was about to inherit the number-one seat at Tyrrell from Jackie Stewart, and he was also being eyed by Ferrari. This was the 1973 United States Grand Prix; he seemed on top of the world on that Saturday morning. Francois gave Helen [Stewart’s wife] a big bear hug when she arrived in the garage. By qualifying, however, his mood had become much less gregarious, he was pensive and quiet – something was on his mind. I shot him backlit as he sat in the cockpit with his balaclava on. I used a longer lens, which isolated Jackie and Derek Gardner, who were bending over the car in deep conversation about setup. The last frame of the film was 26A, Francois’ eyes looking through me into the distance so deeply it was chilling. He then blew Helen a kiss and slipped onto the track. Less than two minutes later, all went silent. The horror was implausible and nothing for me would ever be the same. That photo, I feel, links us for all time. After that, I held back a little bit. I didn’t want to get too close to the drivers anymore.”

For over 30 years, many of Richard’s emotional and elegantly composed pictures lay unpublished. He moved away from full-time photography to work for a spell as a US public relations executive for Mitsubishi, but in recent years has gone back to his archive, held an exhibition in Hong Kong, and in 2018 published a book of his pictures titled Waiting.

He has also gone back to the race track with his Nikon, shooting at the Macau F3 Grand Prix in 2013 and Formula One in 2017 and 2019. Once again, he identified the up-and-coming stars, becoming close to Max Verstappen, Charles Leclerc, Antonio Giovinazzi, and 22-year-old British Ferrari Academy driver and F1 hopeful Callum Ilott. “With Maxy and Charles in particular, I see a lot of parallels between them and the top guys from the ‘70s, like Lauda. It’s rewarding for me to create new digital work, in both monochrome and colour, that captures a whole new generation of heroes and the challenges they’re facing, with emotion, patina and nuance.”

Photos: Richard Kelley © 2021