1972 – Jägermeister Racing turns a wheel for the first time

In the 20th century, there wasn’t a decade that passed without revolutionary change to the established order. Scientific breakthroughs, military conflict, or simply changes in mentality resulted in all sorts of social upheavals that liberalised norms, emancipated certain groups, and - in general - made life statistically better for everyone. Each decade brought something new. The dawn of the aristocracy. The end of racial segregation. Progress for women’s rights movements, or the idea that a man can have long hair, a moustache, sideburns, and a shirt unbuttoned down to his belly button and still be considered attractive…

A lot has happened, specifically during the 1970s; a global fuel crisis, the end of the war in Vietnam, the launch of the MK1 Golf GTI, the televised resignation of an American president, a Polish cardinal elected Pope, and the creation of Apple Computers in a garage somewhere in California. However, in Germany, 1971, well before most of that, Eckhard Schimpf was on his way to neighbouring Wolfenbüttel to meet with his maternal cousin Günter, who happened to be the boss of the Mast distillery; a company whose most famous product was a then-relatively unknown herbal liqueur called Jägermeister.

At that point in time, “Ecki” – as friends call him – had already been rallying and racing for the better part of a decade, but due to budgetary restrictions, this was mostly as a co-driver and only in events which allowed the drivers to switch places. Racing in such a random variety of cars, usually depending on who graciously let him jump behind the wheel, he was never able to really master any of them. For Mr. Schimpf, the time had come to try and find proper money, and either kick things up a notch or give up altogether.

At the same time, Germany was debating whether to allow companies to sponsor football clubs – formerly a taboo subject – just as Günter Mast and Jägermeister were about to make a venture into the sport by sponsoring Eintracht Braunschweig, a Bundesliga club that from 1973 onwards would play with The Stag on their jerseys. Ecki figured that the same could be done with racing cars. “Just give me some money to drive in the Monte Carlo Rally, and I’ll put a few Jägermeister stickers on my car,” he said. And his cousin, who understood the great marketing potential of backing sport, agreed.

Fast forward to January 21st, 1972, and Eckhard Schimpf was on the starting line of the ‘Monte’ in a brand new, dark green Porsche 914/6. Disappointingly, he would not finish the rally. Günter Mast was unhappy; not with the car’s retirement, but its colour. It did not pop, therefore failing to achieve the promised visibility of the advertising. Fortunately, the orange stripe of the sticker put on each Jägermeister bottle acted as a quick inspiration, and the car was repainted in a livery that would achieve icon status in the years to come, while a budget for further racing operations was also established.

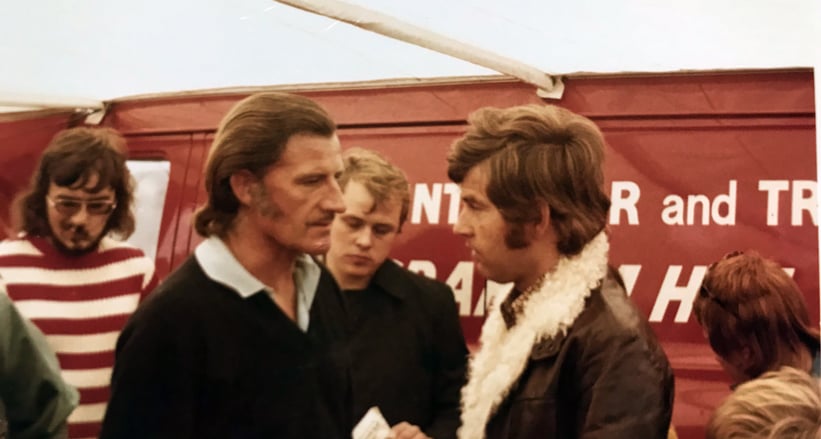

Two months later, on April 16th 1972, former two-time Formula 1 World Champion Graham Hill officially touched down to race for Jägermeister in a Brabham Ford BT 36 (and subsequently a BT 38) in Formula 2. The contract? 170 thousand marks for the 1972 season. This was 130 thousand marks less than what was paid that same year for a racehorse to be renamed “Jägermeister”. But as Hill said, he agreed because: “I’ve only got two legs, and I suppose that the horse has four.”

An iconic livery that was more than a marketing effort

Motorsport today is very different from what it used to be 50 years ago. For example: you didn’t have to go through a drivers’ development programme from Karting to Formula 2 and graduate on top of your class to find yourself in an F1 car. Many aces of the day raced in F2 as well as in F1 and touring cars. They took part in sprints, endurance races, and rallies, and even held regular jobs, like Jägermeister driver Manfred Trint, who was an airline pilot and only raced during layovers.

A lot less money was involved, so big companies weren’t in a position to dictate contract restrictions to protect their investments. Jägermeister’s sponsorship idea was innovative (although at exactly the same time, another alcohol brand hailing from Italy was thinking similarly), but as races were not widely televised, and the internet didn't exist yet, it didn’t make any sense to over-invest. In other words, there wasn’t enough money to create what we’d call a proper team today.

Ecki did have a budget, but while it was subsequently raised, it was so lean that he had to spend wisely. This meant limiting appearances of orange cars, which were either bought or rented, and repainting the livery just before crucial races or series. Hence, over the years, the company entered into agreement with many fully-fledged teams, which would build, service, and run orange cars, either during a season or just for a few races.

The same went for particular drivers, which was only possible because racing was a lot less formal than it is now. Things were often agreed over the phone or by a quick exchange of letters. Schimpf also never made one pence from his role as Head Honcho. For him, being able to participate in races was enough of a reward. Meanwhile, he worked as a motoring journalist alongside his racing to be able to pay the bills.

It should not be surprising that in the 1970s, an Alpina-Jägermeister BMW CSL was a springboard into Scuderia Ferrari for a chap called Niki Lauda. And then from 1972 onwards, Ecki always tried to sponsor ambitious privateers, like Willi Bergmeister in his NSU TT, and Ernst Maring, who built and drove his own cars. Ecki also sponsored women that empowered others to enter the world of motorsport; rally driver Susanne Kottulinsky, or Formula V driver Ines Muhle. Eccentrics like Frank Gardner, who brought a Chevy Camaro to the German Racing Championship, and Dieter Bohnhorst, with his race-prepped DeTomaso Pantera, also raced under The Stag.

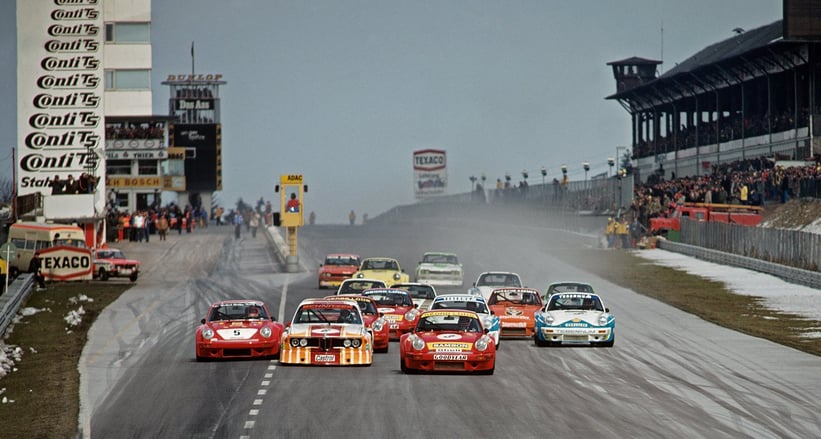

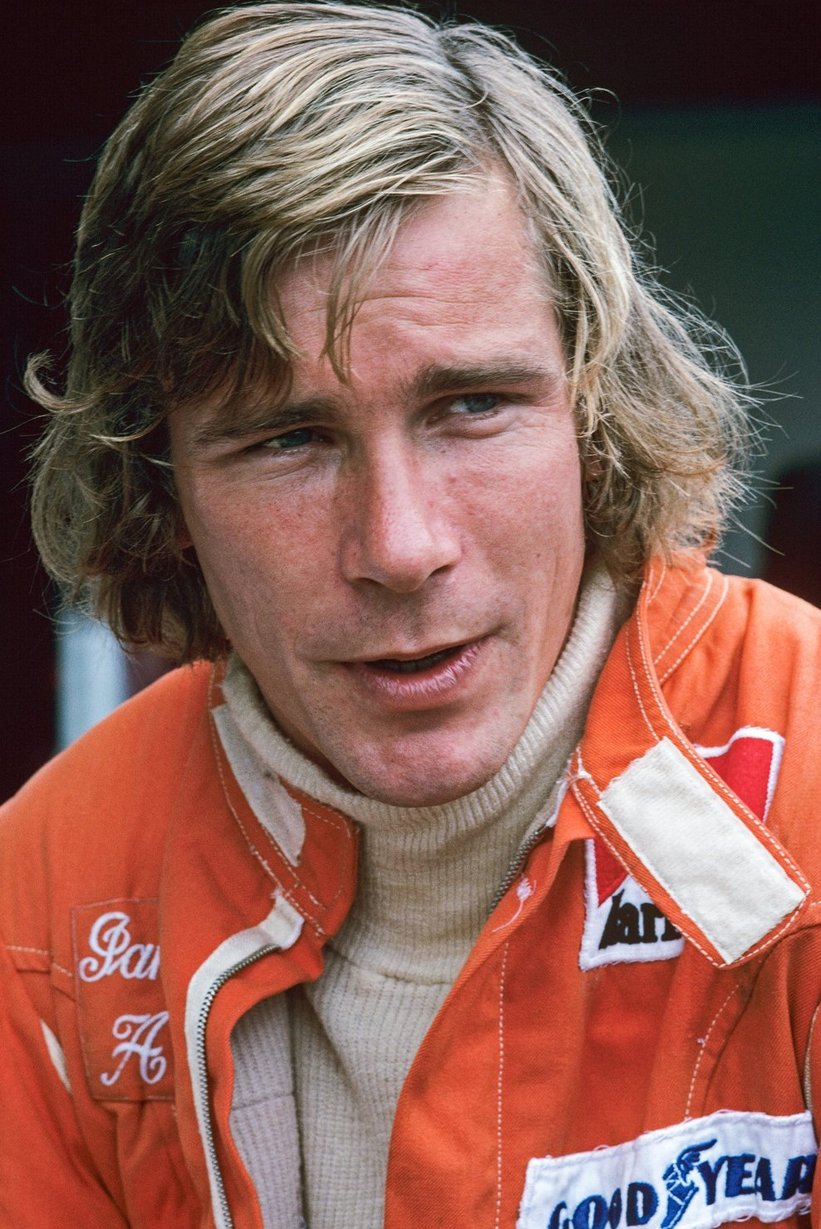

And just as changing cars and sponsorship colours was a fairly normal occurance in the 1970s, the drivers that sat behind the wheel of the iconic Jägermeister cars also varied. Names included Vic Elford, Hans-Joachim Stuck, Manfred Schurti, Jacky Ickx, Rolf Stommelen, Derek Bell, and James Hunt, driving the likes of the Porsche 917/10, the Group 5 BMW 320, the Formula 1 March, and all other naturally aspirated or turbocharged Zuffenhausen-made monsters like the RSR, the 934, or 935 Turbos.

Moving with the times

The 1980s were a decade of excess. Offshore powerboats and white Ferrari’s in Miami. Skaters with Sony Walkman’s, trying to look like Marty McFly. A cable-based music network called MTV bursting onto the scene in 1981, changing pop-culture forever. America losing its war on drugs, and people losing their common sense, wearing moustaches and mullets. These are just a few snapshots from the 1980s. In racing, however, everyone was talking about the ground effect cars of Group C.

Before this revolution, Jägermeister was involved with teams like March, Alpina, Faltz, Max Moritz Porsche, GS Racing (mostly using BMW’s, including an M1 Procar with Kurt König behind the wheel), and at the turn of the decade, Kremer. Bob Wollek drove like a devil in the iconic K3 and K4. But now a venture into Group C had to be made, and Klaus Ludwig behind the wheel of a very uncompetitive Ford C100 ran under the Zakspeed banner. The car was so bad that, for half of 1982, the team returned to the iconic Turbo Capri in order to figure out what was wrong. The C100 turned out to be botched beyond salvation, and as the Capris could still deliver solid results, 1983 saw their return to the DRM, wearing orange of course.

Then a moustachioed gentleman named Walter Brun came along. He had been running a team that could be seen as the living embodiment of 1980’s excess. Brand new trucks, heated tents with hard floors, catering for VIP guests flown in from top restaurants, and up to five cars – Porsche 956s and later 962s – cared for by a crew of around 120 people. Brun, who was used to a lavish lifestyle – often travelling with his wife and his mistress to hotels, where he would demand “a very wide bed” – wanted to pay as much as 30 thousand marks per race to rising racing star, Stefan Bellof. A tough negotiation indeed for Ecki.

Fortunately, Jägermeister saw Team Brun’s potential – Bellof, Stuck, Larrauri, Boutsen, Bell, and future F1 star, Gerhard Berger, all racing together under the orange banner. The budget was raised again, and a string of successes followed. Brun's Porsches would win the World Sportscar Championship in 1986, ahead of factory teams such as Jaguar, Nissan, and Mercedes. No wonder, then, that the relationship between the two companies lasted until the end of the decade, when Brun moved to Formula 1. An idea which unfortunately ruined him.

Jäger-Tonic

In 1989, the Berlin Wall came down and the world woke up to an exciting vision of a worldwide neoliberal paradise. “The end of history” as we knew it. Nothing could stop economic growth and globalisation. Jägermeister must’ve felt that too, as new markets were opening up, even in Germany itself. In the 1990s, Ecki’s budget rose to well over a milion marks per season, which was still modest compared to other teams. Ace of Base “All that she wants” was blasting from radio as Jägermeister made its move into the world of DTM.

As Group C was getting managed to death by the FIA, DTM was now the racing series to be in: technologically advanced, extremely spectacular to watch, and packed with factory teams. Audi, Alfa Romeo, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and Opel all competed in races where 40 vehicles would go wheel to wheel, mesmerising fans. Ecki wanted in.

A deal was first made with Opel, which ran a slightly inferior V6 Omega. Then The Stag moved to BMW with team Lindner, as their budget of 600 thousand marks, 400 thousand below the standard in 1991, wasn't sufficient to sponsor Schnitzer. Fortunately, drivers like Armin Hahne and Wayne Gardner – a former motorcycle champion – put on a good show at each race, which made Wolfenbüttel very happy.

However, the 1990s belonged to the legendary four-wheel-drive 2.5-litre V6 Alfa 155 TI’s, which achieved peak power at a screaming 11,800 rpm. The talented Michael Bartels was the contracted driver, and he quickly became a fan favourite in his orange car, even in Finland, where the words “Jäger-Tonic” had to be put on the bonnet due to a nationwide alcohol advertising ban.

As years progressed, however, the DTM was getting more and more expensive as the cars became more complicated and fragile. The series eventually turned international and changed its name to the ITC. Races were held as far as Japan, a place where Jägermeister was completely unknown. Unable to find a solution that would work with their budget, the company took a break. First in 1997, and then in 1999, before completely retiring all racing operations by the year 2000.

In between, however, there were ventures into other racing series like a season in the STW, with Christian Menzel and Prince Leopold von Bayern in a E36 BMW 320i, and when the DTM finally reinvented itself in the year 2000, with a V8 Opel Astra and Frenchman Eric Hélary at the wheel. Even though the Mast company had grown along with its marketing budgets, one thing was apparent: in the 21st century, to go racing you had to either fully commit or resign. Unfortunately, investing millions into a relative niche sport was something that Jägermeister just wasn’t prepared to do.

Eckhard Schimpf understood and maybe even welcomed this decision. After all, he was already 62 years old and had retired from competition. It should be remembered that he was the team representative for the better part of three decades, simply because he enjoyed it. Thanks to him, his cousins, and all the other heroes who risked their lives just to satisfy the need to go fast, we are now able to tell this story and claim that orange cars do in fact drive faster.