Most of the people who like to use their classic cars regularly either keep them in very good, original shape, or spend hundreds of thousands of euros on restorations. Sometimes, they even subtly improve them – in a move frowned upon by purists – by adding a synchromesh gearbox, power steering or a discreet air conditioning unit. But not Professor Claus Anderhalten. He is what one would call a mega-purist.

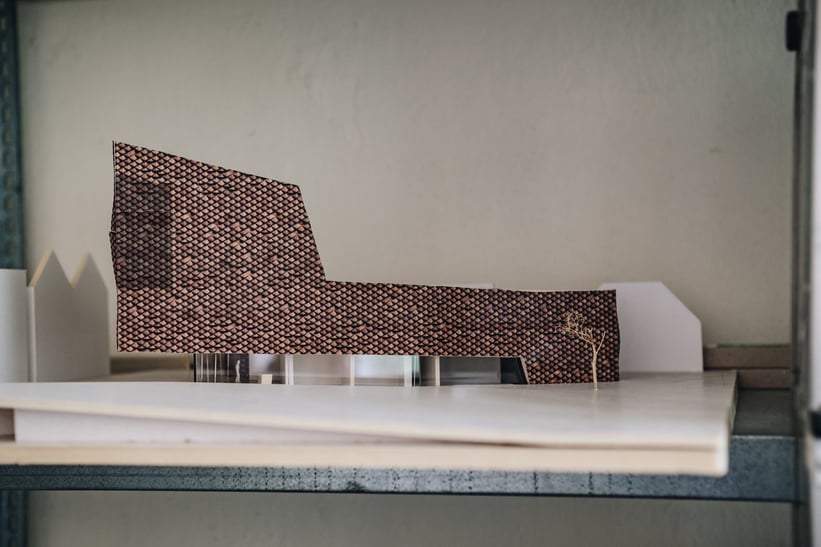

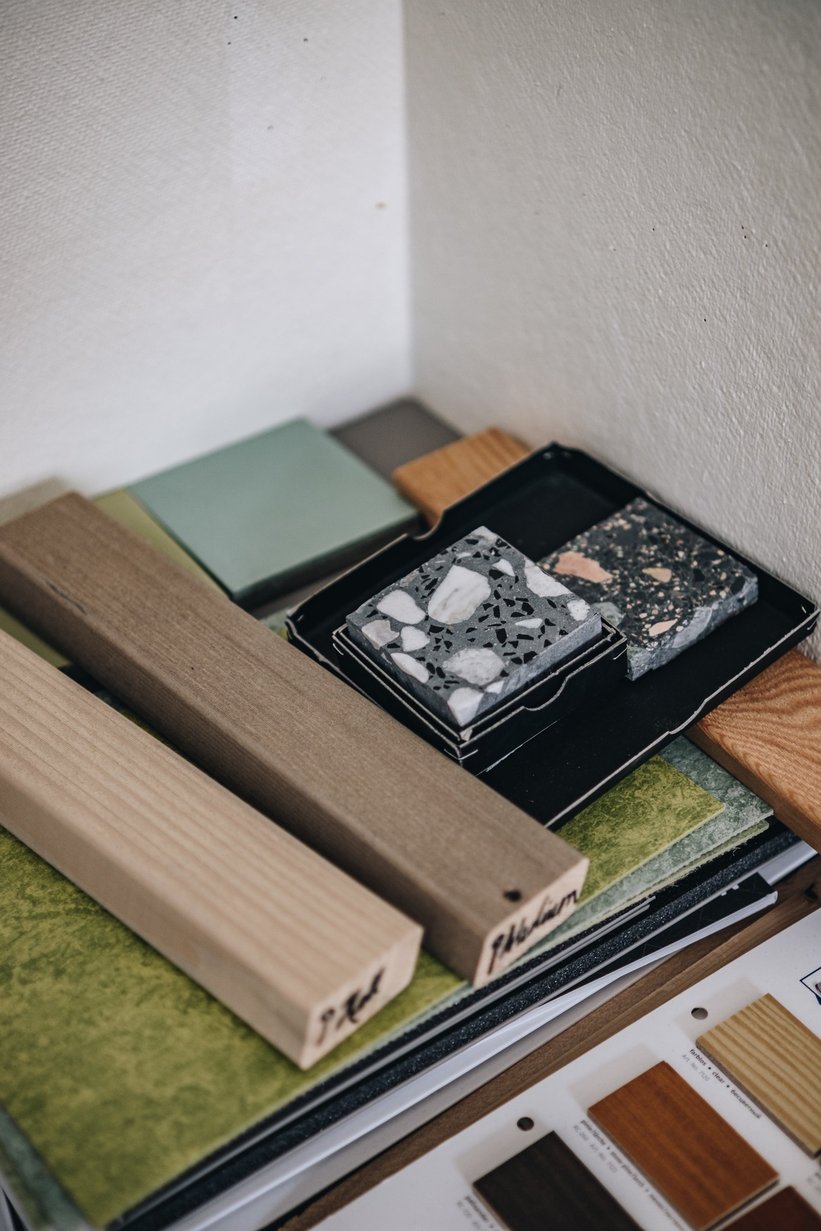

We first met Claus at a Flitzer Club meeting in Berlin. As it turned out, he is the founder of Anderhalten Architekten, a bureau specialising in the restoration and adaptation of historical buildings – although Claus hates being labeled this way, as he has also created many modern structures like the clay-walled Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft in Berlin. And while the principles that guide him in his professional life are ones of modernising, restoring and improving the functions of existing constructions, he has adopted a completely contrary approach to collecting cars.

And as a collection of 25 cars is very hard to maintain, it should come as no surprise that most of Claus’ cars don’t work. Some of them are in boxes. Others could, in all fairness, be called rust buckets – although he once claimed “rust is good” during a Flitzer Club meeting. One of two Maserati Ghiblis he owns is currently undergoing slight restoration and three to four machines, like his 1964 Porsche 911, are in a “sort-of-running” condition.

Three to four running cars seem enough, which allows Claus to optimistically assume that they will make it no matter the journey. An approach, which in turn either leads to scenes of prominent Flitzer members pushing him to a start when the cars eventually fail to proceed, or to Andreas – the volunteer Flitzer mechanic – pulling all-nighters during the club’s many outings, while trying to fit an express-shipped, electric radiator fan to Claus’ 1962 Mark I Jaguar E-Type, for example.

“I was on the highway just off Lake Constance, approaching the Swiss border when I saw some bits flying off my my car” Claus recounts. “Later on it turned out that my original, belt driven fan had snapped, and so a quick fix had to be performed on the parking lot of the hotel in Zurich. Thank god for express courier services” – he laughs, shrugging it off like nothing had happened.

Naturally, we struggle slightly with the mechanism of the fold-down windshield of one of his five (!)Austin Healey 100/4 – the one that just about works – before setting off on a tour of the amazing Hansaviertel district of Berlin, in which Claus owns one of the case study houses. Built from 1957 to 1961 as a social housing project by international master architects such as Alvar Aalto, Egon Eiermann, Walter Gropius, Oscar Niemeyer, and Sep Ruf, one of Berlin’s smallest disctricts was literally constructed on a part of land that was razed to the ground during World War II. An architectural pearl with streets named after cities that were part of the Hanseatic League. A perfect classical-modernist landscape for a professor of this organisational and space-shaping artistic discipline that is architecture.

But before we have a chance to settle down to talk about different philosophies of collecting, we’re being told to leave by an Amazon film crew filming a period piece on the streets of the photogenic neighbourhood. We depart in a cloud of noise (straight-pipes on the Austin), just to catch our breath on the district’s outskirts under the striking, Paul G. R. Baumgarten-designed maisonettes of Eternit-Haus.

Claus immediately enters professor mode and points to the attractive glazed studios on the top floor and private rooftop terraces, installed to save space in absence of regular gardens. But I want to get back to cars. “It’s fairly simple” he says “I’m only interested in the very earliest VIN numbers, because they constitute the purest idea of what any particular model was supposed to be. They are closest to its creators original intentions. Even if they are inherently flawed. When the car gets improved further down the line, for me, it stops being interesting” he remarks.

We jump into the Healey yet again – quite literally, as my door opens only some of the time – and drive to Claus’ top secret storage facility, a garage somewhere in Kreuzberg, to quickly switch to one of his two E-Types. As it turns out, the Austin is too low to get up the garage’s ramps and we end up scraping bottom. His quick fix? Take a very smokey Triumph TR5 up the ramps, as it beats walking, push the Healey where the Triumph slept, and then exchange the “five” for the Jag. Easy.

This complicated operation allows me a glimpse of a small part of the “mad professor’s” collection. One of the two Fiat Dinos, a red coupé, smiles at me, while the other one is invisible underneath many boxes filled with car parts. A Maserati Khamsin engine lays on the floor next to a Lancia Flaminia GT, which may or may not have been driven by some Italian celebrity, which lead Claus to buying it, while he was shopping for parts for one of his seven Maseratis – including two Ghiblis, a Khamsin, two 3500 GTs, and a Mistral. And this is only the tip of the iceberg.

Personally, I find it amazing that Claus seems to be perfectly relaxed in a situation which would give me a level of anxiety that would keep me in bed for the remainder of my life. The fact is: all these cars, no matter the state they’re in, spark joy for Claus. So an automotive Marie Kondo would have gone nowhere trying to clean up his act. Every time he points to a specific item on the list of cars he shows me in his phone, his eyes light up with excitement. I’m sure that he hopes to be able to repair or restore most of these machines at some point in time. In this case, I’m happy to settle at intentions counting.

As it’s time to say goodbye, while he explains to me why the Moss gearbox in the Jaguar is “actually better exactly because it is terrible” than any unoriginal replacement that actually doesn’t grind with every gearchange would ever be, as “this is the closest you’ll ever get to actually feel what it was like to drive there cars in the period”, he makes me promise not to reveal his car hoarding habit to the world. Oops!

Photos and words by Błażej Żuławski © 2022