"One can justifiably assert that without graphic designer Erich Strenger, our idea of Porsche’s brand history would be rather different."

Assumptions about alternate realities are always a delicate subject in journalism. But in this case, one can justifiably assert that without graphic designer Erich Strenger, our idea of Porsche’s brand history would be rather different. Between 1951 and 1988, he formed the corporate design language of the Stuttgart marque with his countless artistic designs. Whether it’s a Porsche 356, an early 911, or a Le Mans prototype, such as the 917K, we can’t imagine these cars without Strenger’s drawings and collages also coming to mind.

A cooperative starting signal

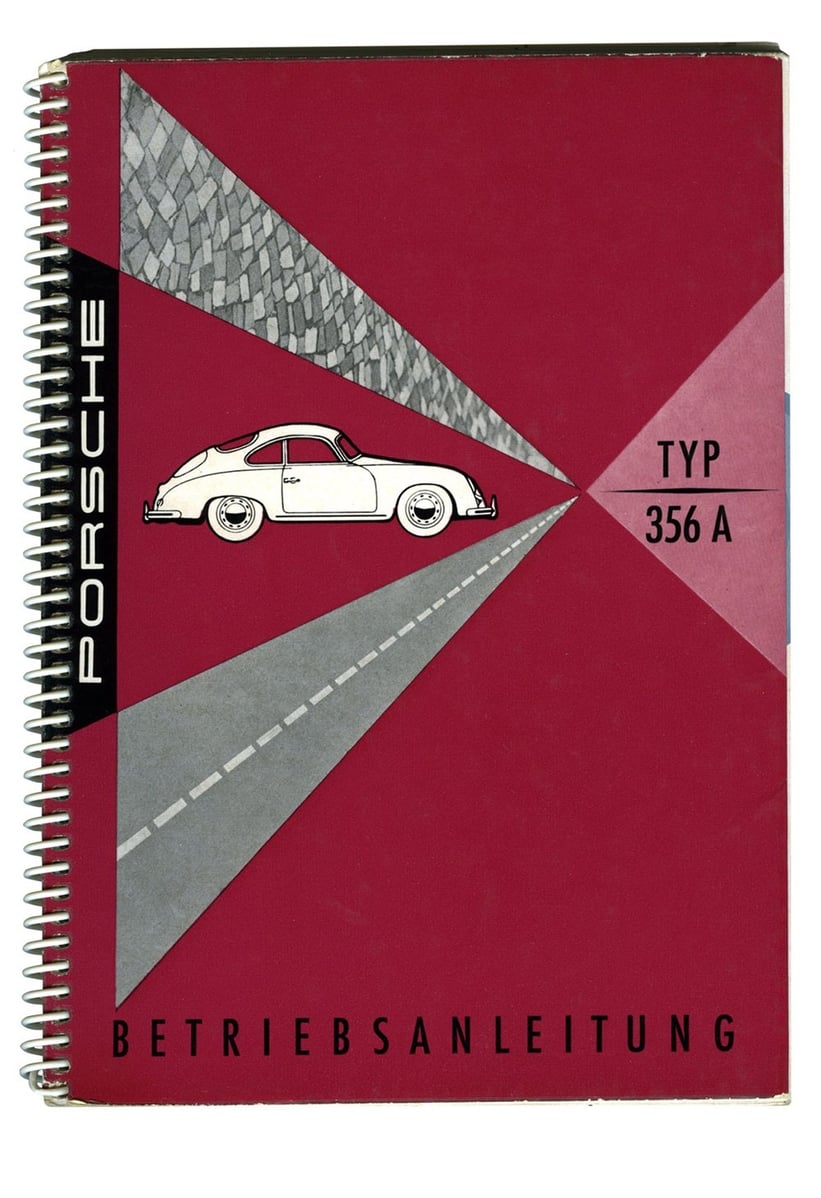

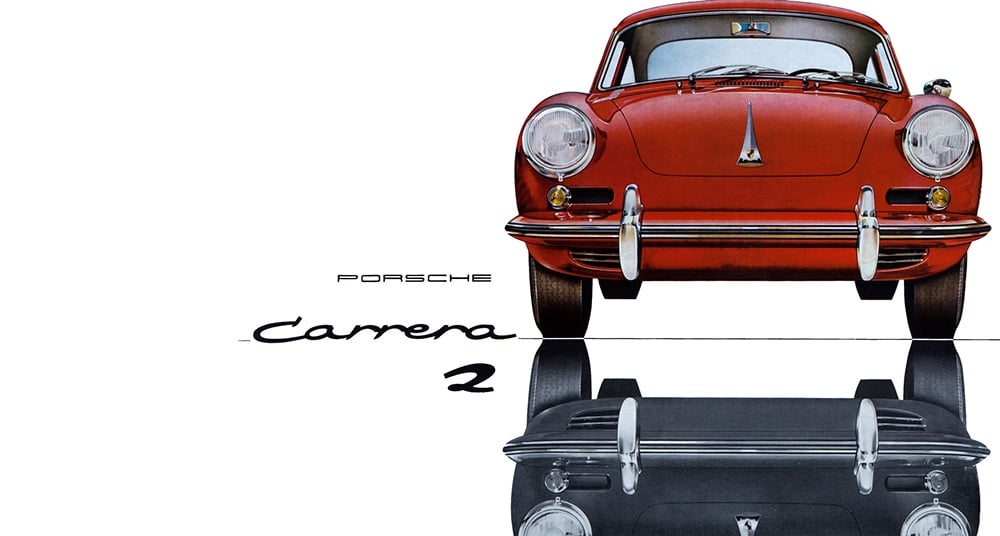

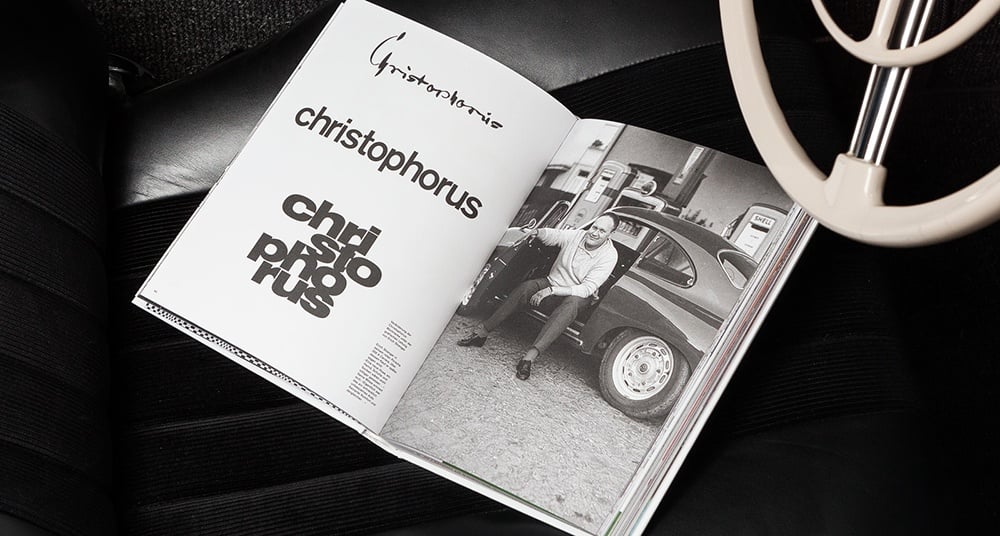

The starting signal for the long-term collaboration sounded in 1951, at a beauty pageant in Stuttgart. Strenger and historian Richard von Frankenberg, who had just begun to form Porsche’s communication department, discovered their common enthusiasm for the brand and soon forgot about the ladies up on the stage. Since Porsche preferred to invest money in motorsport rather than expensive ads, attractive sales brochures were the means of choice to promote new models at trade fairs, and Strenger’s first work for Porsche was a hand-drawn brochure for the 356 Coupé. The full potential of the partnership was realised in 1952, when Strenger and von Frankenberg established Christophorus — the first in-house magazine from a German manufacturer, which is still read by Porsche enthusiasts around the world to this day. Named after the patron saint of all motorists, the magazine became a development lab for the brand’s visual identity. Here, Strenger could work more with abstract collages or engage artists to design striking front pages. And the cars weren’t always in the foreground.

When lettering travels the world

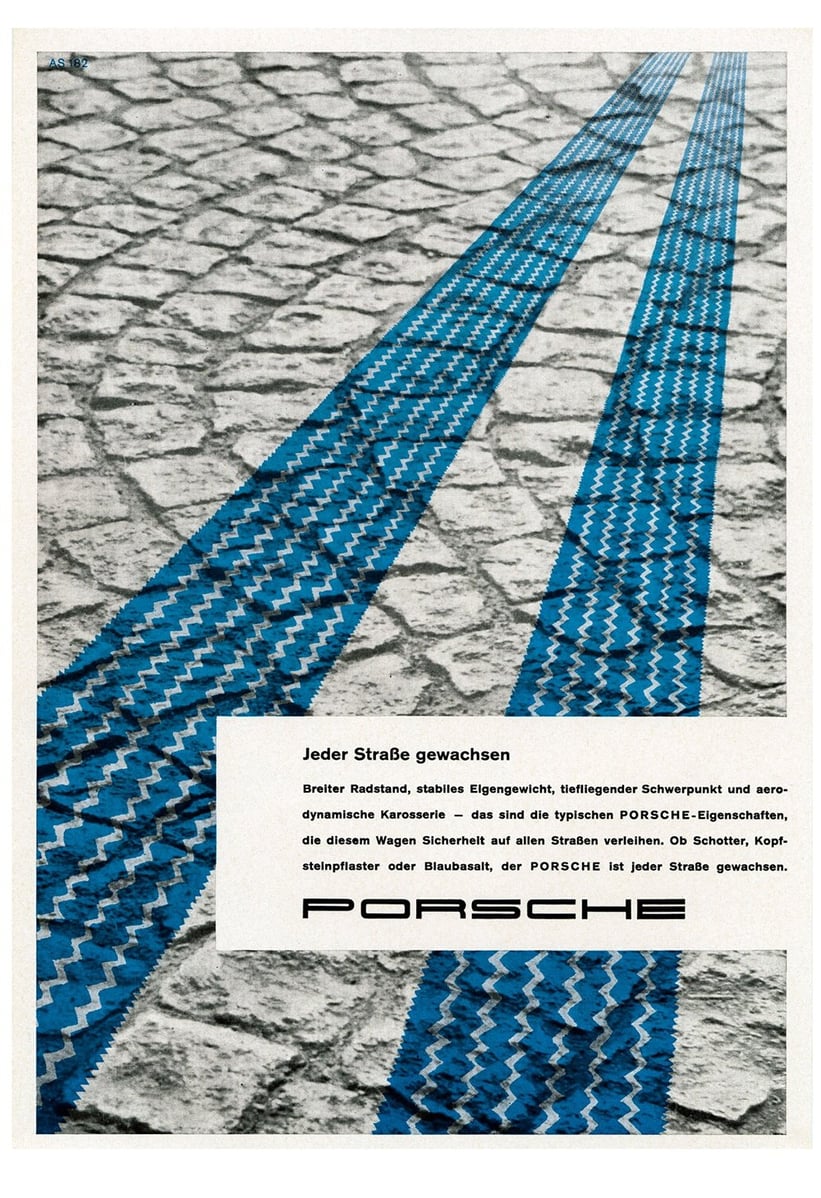

At the beginning of the 1950s, Porsche’s brand name was typically handwritten on the brand’s advertising material. Strenger quickly developed a new, more modern and universally applicable typography — his Porsche logo has remained almost unchanged to this day. Furthermore, Porsche’s official house colour, a Bordeaux named HKS17, originated from these early designs. Over time, more and more models were rolling out of Zuffenhausen and promotion strategies were changing. Photographs of the cars began to be shown rather than drawings, and starting in the mid-1950s, Strenger developed the first creative ads, which could be used by Porsche dealers to advertise in their local newspapers.

From the race track to the bedroom wall

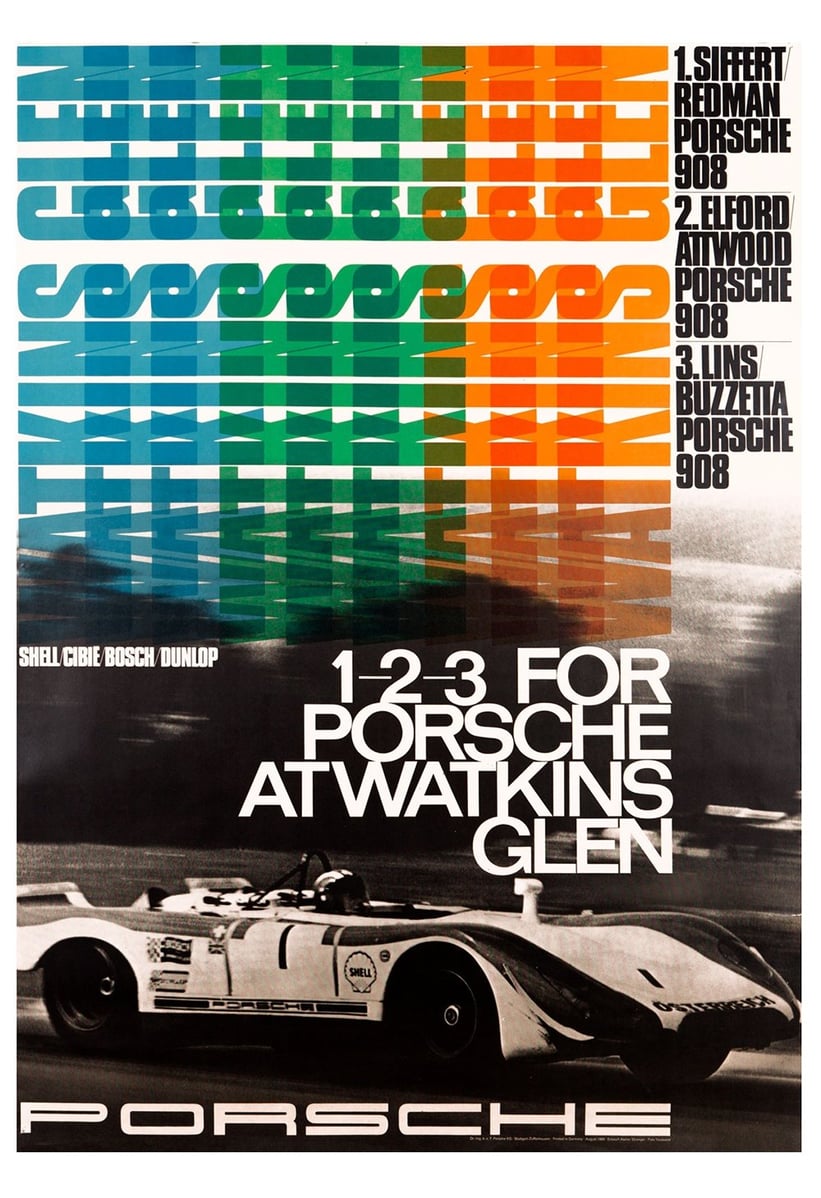

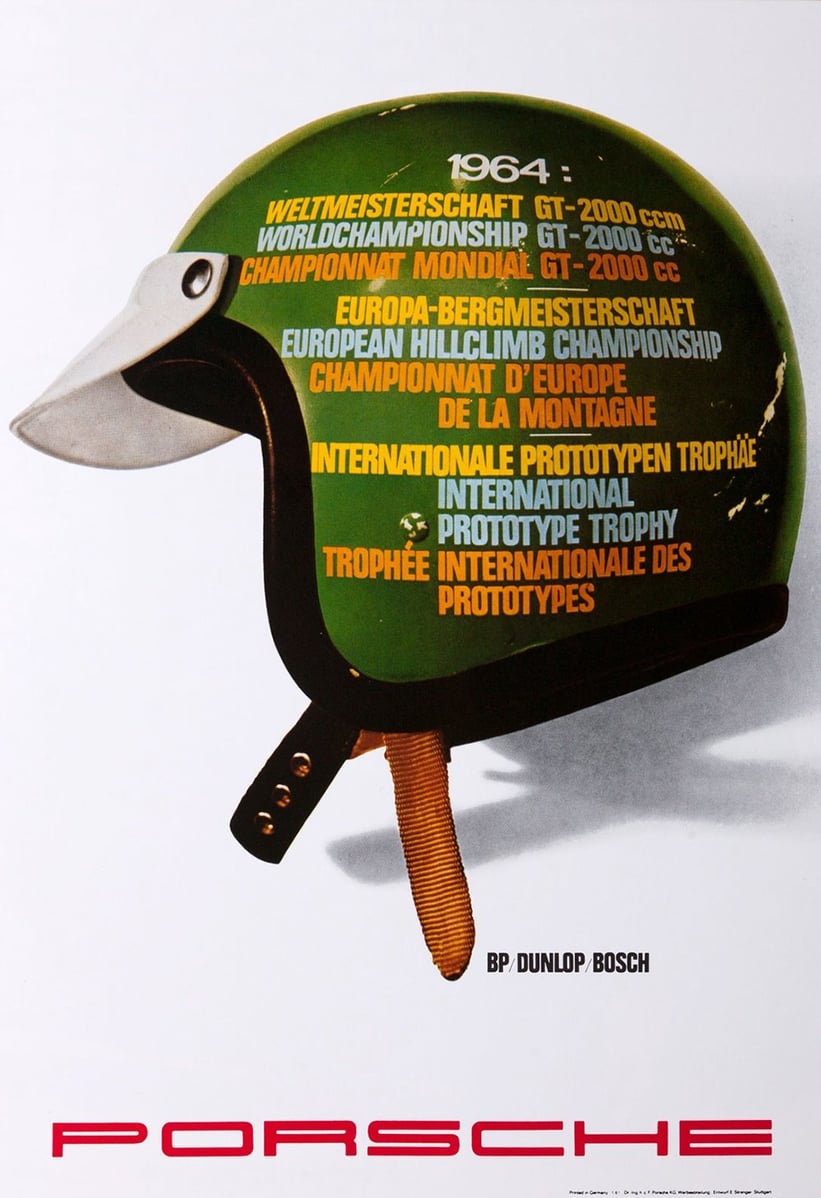

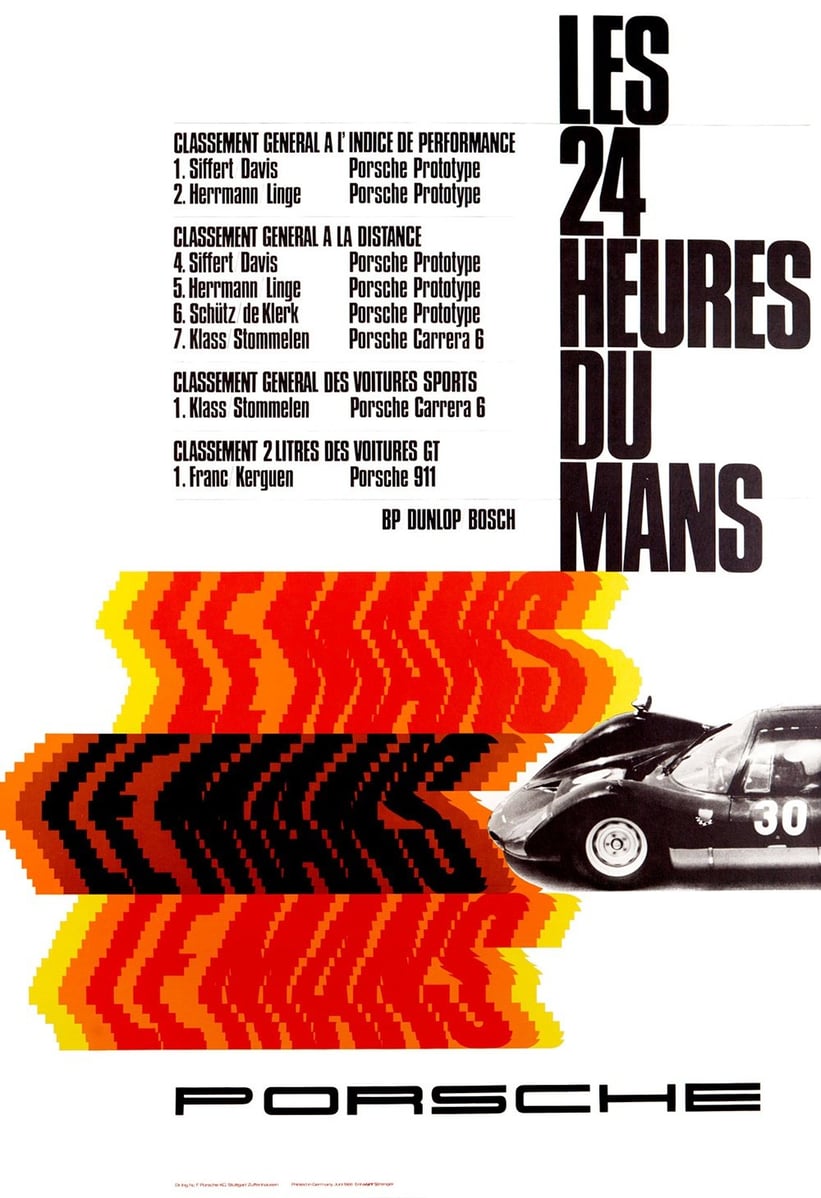

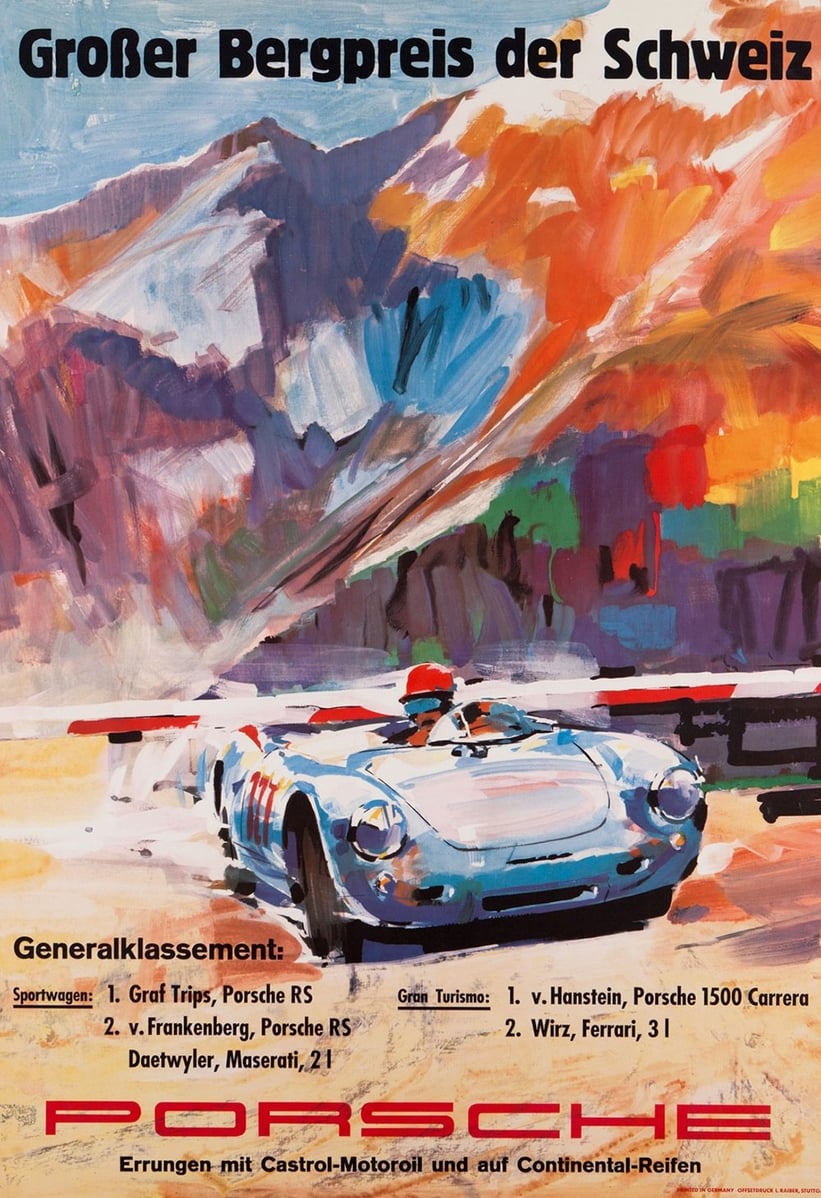

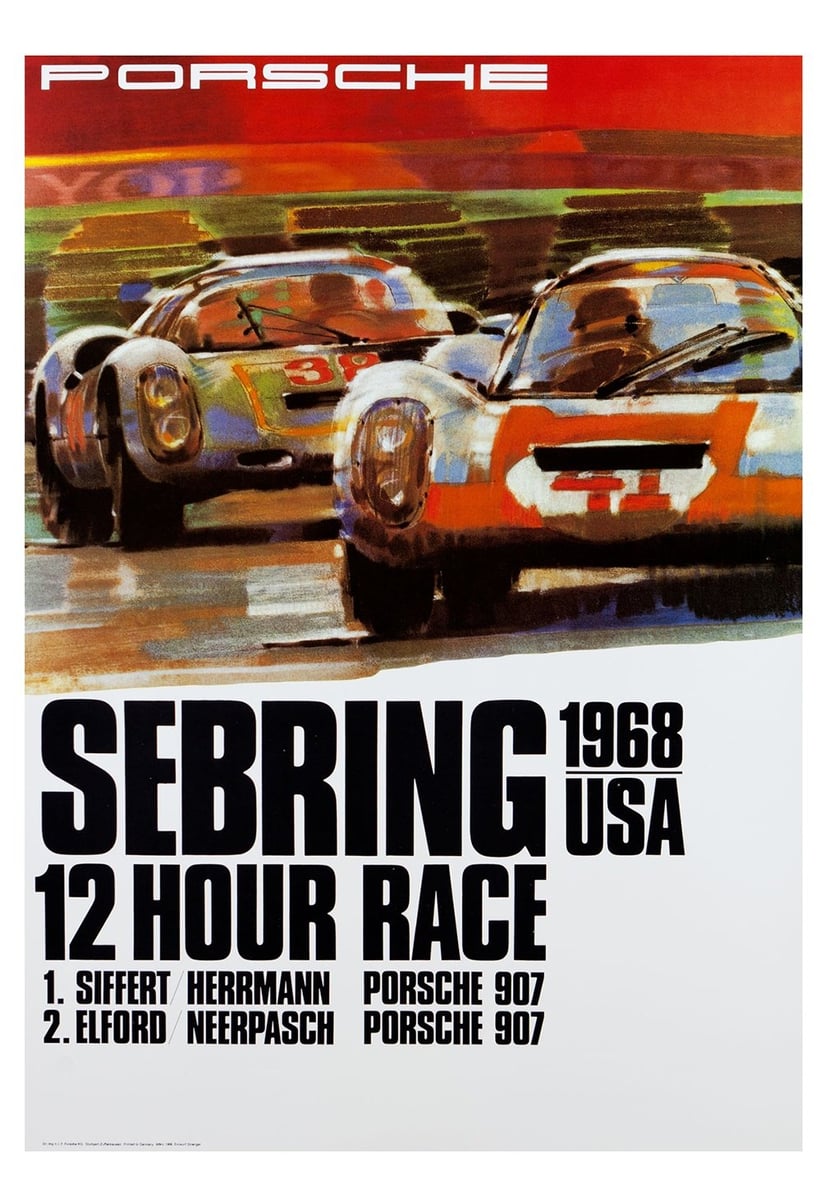

At the same time, motorsport remained Porsche’s most important field, providing an opportunity to demonstrate the sportiness of its machines. Porsche’s famous racing director and public relations manager, Huschke von Hanstein, ordered a poster from Strenger for each race. The posters, which usually had to be in the printing presses the following day, portrayed the most important moments from the Targa Florio, Le Mans, and the Monte-Carlo Rally, and found their way onto the bedroom walls of countless young men, all of whom were subsequently ‘infected’ with the Porsche virus. Up until the 1980s, Strenger designed countless artistic racing posters for Porsche, reflecting not only his graphic talent but also his inexhaustible creativity.

With the arrival of new management at Porsche, the Strenger era came to an end in 1988. He and his wife took leave and emigrated to Spain, where he had plenty of time to enjoy the most beautiful things in life and surrender to his secret love: abstract painting in the op art style.

A graphical report

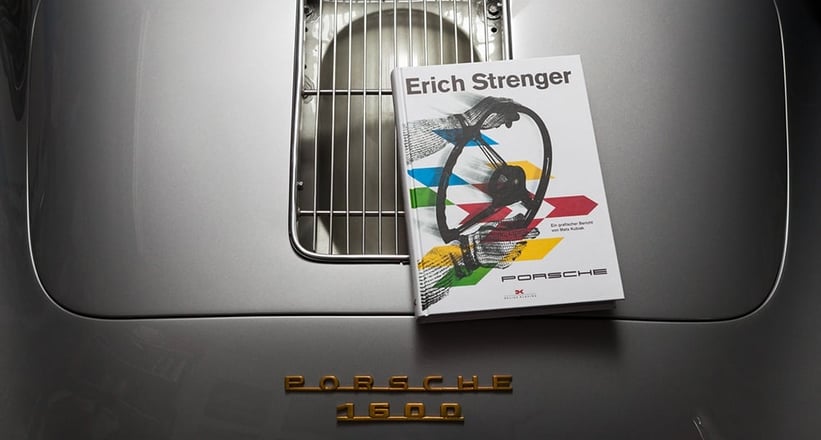

In his recent book, Erich Strenger and Porsche: A Graphical Report, published by Delius Klasing, author Mats Kubiak explores the creative work of the graphic artist, providing an overview of the four decades that shaped the young company’s brand communication. “The book project began to take shape during my undergraduate degree in communication design,” says Kubiak, who grew up on the back seat of a Porsche 356 and now runs a design agency in Düsseldorf. “It was a great logistical challenge for me and quickly turned into a huge undertaking.”

The real reason for the book was due to the fact that Erich Strenger’s work for Porsche had never been uniformly documented, let alone digitised. “As a Porsche fan, my wish was to make Strenger’s work accessible to the public for the first time,” comments Kubiak. “Since digital reproductions were missing, I had to look for Strenger’s work all over Germany and create reproductions — a painstaking endeavour. However, this helped me to meet former companions and friends of Strenger, all of whom had exciting stories to tell. This finally led me to Strenger’s widow, who lives on Mallorca.”

A huge body of work

This provided an exciting retrospective collection of the designer’s work, in which anecdotes and stories are illustrated with many photographs and illustrations. “The book’s not only about Strenger’s work, but also a biography of his life, because both are intertwined in his case. His work significantly contributed to the definition of Porsche’s core values — such as sportiness, efficiency, and modernity — as well as the unconditional recognition of the company’s products.” The harmonious design of the book, in which Strenger’s works are graphically staged with the help of collage, only strengthens this impression. “This book doesn’t claim to be an all-encompassing catalogue of Strenger’s work,” admits Kubiak. “It’s rather intended to enable the reader to enter various parts of the chronological sequence and examine individual highlighted works.”

“Erich Strenger’s legacy,” Kubiak summarises, “is an incomprehensibly extensive impression on a broad spectrum of graphic design, which today, just as before, brings a glimmer to our eyes whenever we see an old Porsche 356 or 911 out on the street. In some respects, Strenger was a pioneer in the field of brand communication within the automotive sector. Hardly any other designers at that time created such a comprehensive and interdisciplinary work for a single brand as he did. So, I can wholeheartedly recommend my book not just to diehard automotive enthusiasts, but also to fans of art and design in the era of Ray and Charles Eames and Victor Vasarely.”

Photos and illustrations: Mats Kubiak