For those who like their motorsport muddy, the Sandglow Yellow Land Rovers that competed in the Camel Trophy in the 1980s and’90s are every bit as iconic as the Gulf, Martini and Marlboro liveries that tore around Europe’s race tracks in the golden era of circuit racing.

The Camel Trophy was a collaboration between the all-terrain car maker and the equally rugged Camel cigarette brand that made heroes of amateur off-roaders, pitched nations against one another and brought old-fashioned expeditioning to some of the most inaccessible corners of the globe. It was, essentially, an Olympics of four-wheel-driving.

This week, Land Rover announced it is releasing 25 yellow ‘Trophy’ Defenders, born from the classic-shape vehicles it squirrelled away after production ended in 2016. They feature 400bhp V8s and hardcore kit, including roof racks, winches and roll cages. The eyebrow-raising £195,000 price includes entry into a three-day off-roading competition at Eastnor Castle, Herefordshire, where Land Rover has been testing its models on 66 miles of trails for decades. The company describes it as its Fiorano.

I’ve driven around there and it’s definitely not for the faint of heart, but it’s still somewhat vanilla compared to the challenges faced by customers on the Camel Trophy between 1981 and 1998. For starters, Eastnor has no piranhas, headhunting tribesmen or – to my knowledge – pockets of malaria.

Selection for the Camel Trophy was extremely exclusive; the event demanded mental strength and physical endurance from its participants as well as driving skill. No-one was allowed to compete twice. Over the years, the annual adventure visited Indonesia, Borneo, East Africa, Papua New Guinea, Australia, Madagascar, Siberia, Mongolia and large swathes of South America.

In fact, the very first Camel Trophy, held in 1980, didn’t feature Land Rovers at all. The event was the idea of an advertising agency in Düsseldorf, and was designed to promote American tobacco giant RJ Reynolds’ Camel brand. The route was 1,000 miles through the Amazon and across the badlands of the Brazilian gold rush, from the Atlantic city of Belém to Benjamin Constant, deep in the jungle.

There were just three crews – all West Germans – in three Jeep CJ6s. Legend has it that they were simply rented at the airport, in which case it’s unlikely they got their Hertz deposit back, because none of the Jeeps managed to complete the course.

Word reached Solihull, and for 1981’s raid on the island of Sumatra (which straddles the equator to the west of Indonesia) Land Rover’s Special Vehicle Operations department prepared a bunch of toughened V8 Range Rovers. This time there were five teams consisting of eight men and two women– all German once again. They faced everything along the way, from volcanic mountain ranges in the north to the 10-foot deep rapids and tropical swamps of Sumatra’s south.

The reliable and robust Range Rovers excelled here, andin Papua New Guineathe following year. Thereafter, Land Rover would switch between different models, including the Series III, Defenders 90 and 110, the Discovery in 200tdi and 300tdi form, and finally in 1998, the Freelander. All were kitted out with mud tyres, Hella spotlights, Mantec snorkels, tow hitches, winches, roof racks, roll cages, bridging ladders, Webasto fuel-burning heaters, Terratrip rally computers, GPS, VHF radios, and mean-looking bull bars.

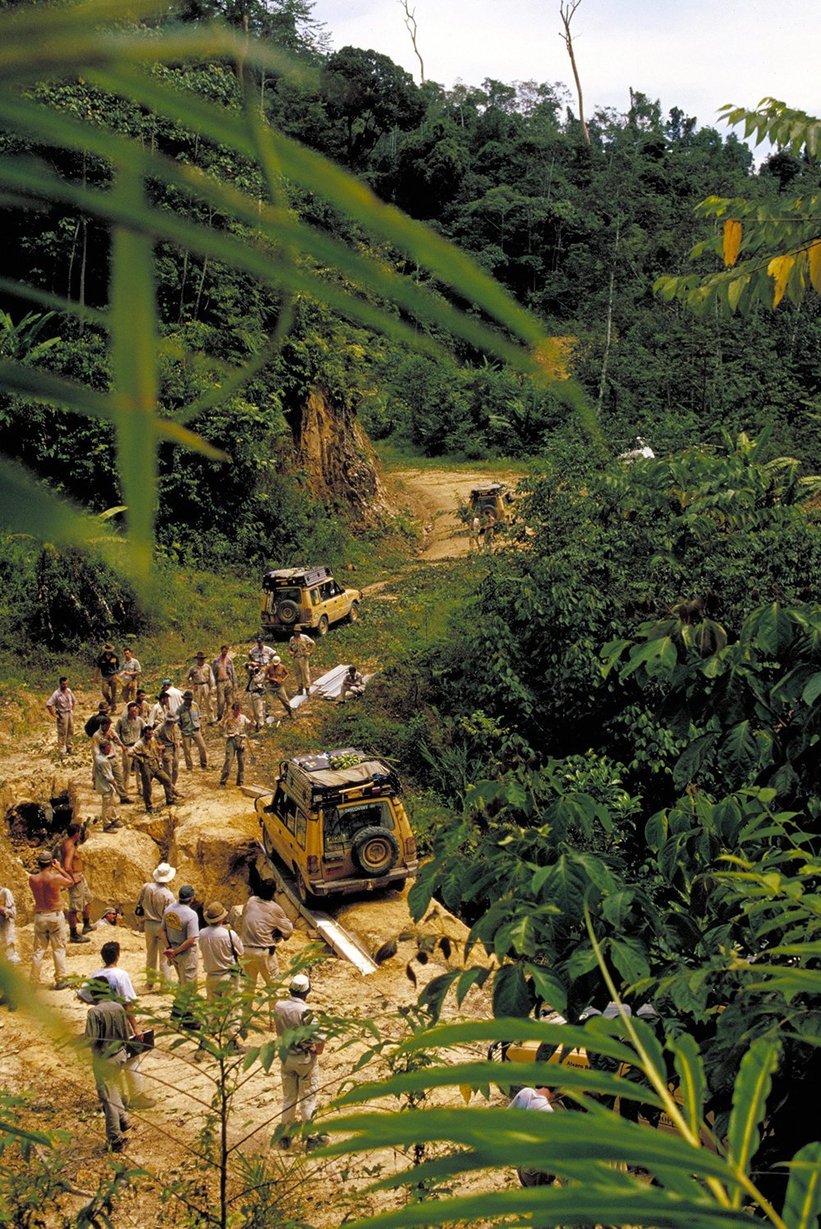

The 1982 event, in Papua New Guinea, saw the convoy become international. There were eight teams, two each from Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and the USA. Points were awarded across 10special tasks to test teamwork, driving skills and endurance, such as time trials, manoeuvring trials and navigation challenges, negotiating perilous slopes and balancing their vehicles on greasy log see-saws, which required precision, patience and panache. That year, the Italians Casare Geraudo and Giuliano Giongo were crowned champions and the members of 700 local tribes lent enthusiastic support.

The following year, teams from Spain, Portugal, Switzerland and Hong Kong joined to battle the most dangerous destination yet: snake-infested Zaire. Here, cars navigated hundreds of miles at a steep angle of incline and frequently turned over. Attempting to make tea in asupporting 109, a journalist knocked over an oil stove, blew up the Land Rover and nearly laid waste to a village.

Upon reaching remote settlements, supplies would be given to locals as well as medical aid. Wells, buildings and bridges would be built, while wildlife and geographical surveys were undertaken by specialists hitching rides with the convoy.

The event’s format was expanded in 1986 to allow more countries to compete, but spots were restricted to one national entry each, for around 14 cars in total. The prize was a brand-new and unspoilt Land Rover of the same model, although in Madagascar in ’87, where the Range Rover TD was used, the winners requested two new Defenders instead.

An additional award for ‘team spirit’ was introduced to recognise those who helped others and imbued the Camel Trophy’s sense of adventure and fairplay, and this was viewed as important as overall victory. Camaraderie is vital when more than a fortnight is being spent thrown every which way in a hot and cramped 4x4, caked in sour-smelling mud or with dust stinging the eyes and carpeting the throat. The bucking and kicking vehicles frequently gotstuck inthe strangling terrainand everyone survivedon aroundfour hours sleep a night.

By the end of the decade, the Camel Trophy had become quite a big deal; in 1989, over a million would-be explorers applied for 28 spots. That year, in a treacherously rainy Amazon which wasjudged to be the toughest Camel Trophy ever, the winners were British brothers Bob and Joe Ives.

Images of tooled-up, mustard-coloured Landies kept adventurous types rushing to dealerships well into the ’90s. I recall two posters I had on my bedroom wall around this time, side by side. One was the iconic image of a white Lamborghini Countach, and the other was of a Camel Trophy Defender smashing its way through a mosquito-ridden rainforest. Both were the dream. My stepfather bought a Defender 110 and sent off his Camel Trophy application form, despite never having tackled anything tougher than Exmoor. Unsurprisingly, I don’t think he heard back.

From 1997, in freezing Mongolia, the focus drifted away from the Land Rovers to tasks such as kayaking, orienteering and mountain-biking. And in 1998, the plucky Freelander surprised its critics on the Tierra del Fuego event, with its light weight helping it skip over snow and ice and glide over mud rather than just plough through it, like the bigger, heavier Discoveries did. But Land Rover was in the midst of being passed around by Rover, BMW and Ford at the time, and so called it quits. Two years later, with the squeeze being put on tobacco advertising, the Camel Trophy was no longer.

Today, surviving Camel Trophy veteran cars are sought after and there’s a Camel Trophy Owners Club. The new £200,000 V8s are possibly more capable than ever, but it’s unlikely they’ll ever be able to tell such jaw-dropping stories.

All images courtesy of Land Rover Heritage