‘Big-banger’ sports car racing, the ultimate expression of which was the Can-Am championship in the late 1960s, was attractive to manufacturers for myriad reasons, not least the virtually limitless regulations and the extremely generous prize money. But Colin Chapman had another thing on his mind when he threw his hat into the high-capacity ring with the Lotus 30: good, old-fashioned payback.

See, when Ford’s top brass announced its intention to beat Ferrari at Le Mans, Chapman was reportedly convinced that he’d get the nod to build the car with which they’d do it. He had, after all, partnered with the Detroit powerhouse to take on the Indianapolis 500. But Ford ultimately plumped for Eric Broadley, whose Lola Mk6 GT appeared to be the ideal foundation on which to build what would become the GT40.

Chapman was understandably disgruntled. So, in a bid to show the world that he was Britain’s number one automotive designer and that Ford had made the wrong choice, he set about building a sports-racing car utilising a backbone chassis, much like that found in the recently revealed Elan, cradling a powerful American V8. The Lotus 30 was born.

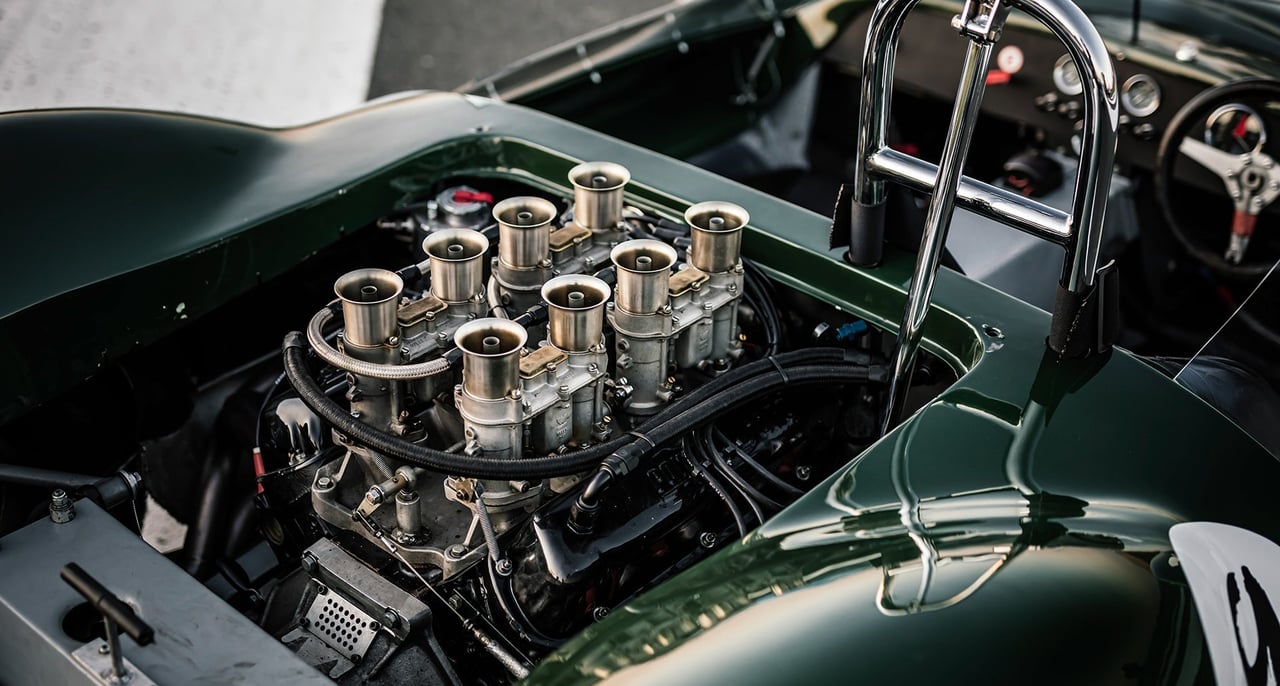

Immediately there was resistance to the project in the Lotus camp. The doubts primarily concerned the strength of the tuning fork-shaped chassis and whether it was strong enough to cope with the torque and weight of the cast-iron Ford 289cu V8, a tweaked version of that found in the Ford Fairlane. Undeterred, Chapman pushed on and presented the finished car at the fifth annual Racing Car Show at London’s Olympia in January of 1964.

Daring. That’s certainly one word we’d use to describe the appearance of the Lotus 30. Immediately obvious is its height, or rather lack of. The remarkably flat Len Terry-designed bodywork, which encompassed seductive curves atop the wheels and a chiselled, angular snout, looked delicate and slippery, just as a Lotus should. (Well, that was until you parked a human in the driver’s seat – exposed isn’t the word for it!)

As promising as the Lotus 30 looked, in practice it was another story. At the top of a long list of well-publicised issues were, as the engineers in Cheshunt had feared, terrifying chassis flex and nightmare handling. The 700kg, 350bhp thunder-ball even got away from the great Jim Clark on occasion, which is especially telling. Woeful unreliability added insult to injury, and begged the question why build something that was never going to work in the first place? Chapman persisted and developed a Mk2 version with a stronger chassis, spoilers and bigger wheels, but the 30 was never a match for the Lolas and McLarens against which it competed.

The way it drove didn’t seem to deter customers from buying Lotus 30s – a relatively high 21 cars were sold in 1964, of which this example that’s currently for sale with ChromeCars in Germany is one.

Delivered new to the car dealership Duchess Auto in New York, chassis L7 was promptly put to work. Newton Davis, who ran Duchess Auto’s Lotus arm together with Fred Stevenson, raced the car – which had been crudely self-modified to try to cure the overheating and handling issues – in the Nassau Trophy in the Bahamas and in several SCCA events. Most notable was a win in a regional event at Lime Rock.

In 1979, having spent the previous decade in storage, the car was sold to one Alex Seldon and returned to the UK, where it was restored, updated to Mk2 specification and raced successfully in a plethora of HSCC events. It actually won the 1980 Classic Sports Car Championship. Since then, L7 has passed through a number of owners both in Europe and the US. Its most recent custodian, a Belgian collector, acquired the Lotus in 2012 and has regularly raced it at prestigious historic motorsport events such as the Le Mans Classic and Goodwood Revival.

“It’s just so damned sexy,” remarks ChromeCars’ Michael Gross when we ask him why the British Racing Green Lotus 30 he’s selling is appealing to collectors today, “and actually it’s a lot bigger in the metal than in looks in photos.

“Back in the day, Lotus 30s usually failed to finish. But thanks to modern restoration techniques, expert race preparation and shorter historic race distances, they’re now seriously competitive weapons. This car, which originally raced at the Bahamas Speed Week, has been at the sharp end of the Whitsun Trophy grid at the Goodwood Revival for many years now. Provided you’re a good enough driver, this could be your winning entry ticket to what is the world’s greatest historic motorsport meeting.”

We’re glad the Lotus 30 came good as a historic racing car – it would have been sacrilege for such a stunning machine to be consigned to a list of cars motorsport history would sooner forget. More importantly, it stands as a testament to Colin Chapman’s vision, ambition, bravery and persistence. He might not have proved Ford wrong with the Lotus 30, but at least he had the guts to have a go. His résumé is hardly lacking in other departments, is it?

Photos: Roman Raetzke for ChromeCars © 2020