This is quite a year for Saab. The company is back from the brink with a new owner and a new car, the promising 9-5. That new owner, Victor Muller, who is behind the reborn Spyker marque, entered this year's Mille Miglia with a 1955 Saab 93, because he just loves the little two-stroke cars. Saab CEO Jan-Ake Jonsson did likewise, in another 93, and the pair of them were cheered right round the route.

What better year, then, for a plucky British team to re-enact the Saab-flavoured story of the 1959 Le Mans 24 Hours? In that year two 93s were entered, their tiny 748cc two-strokes giving them a strong chance in the class for the smallest engines. Originally there was to be just one Saab, a grey machine entered semi-officially by the factory's competition department, but as June drew near a British tuning expert, Syd Hurrell (later to form tuning company SAH Accessories) decided that he and friend Roy North (later to become another car accessories magnate) should enter a second Saab 93.

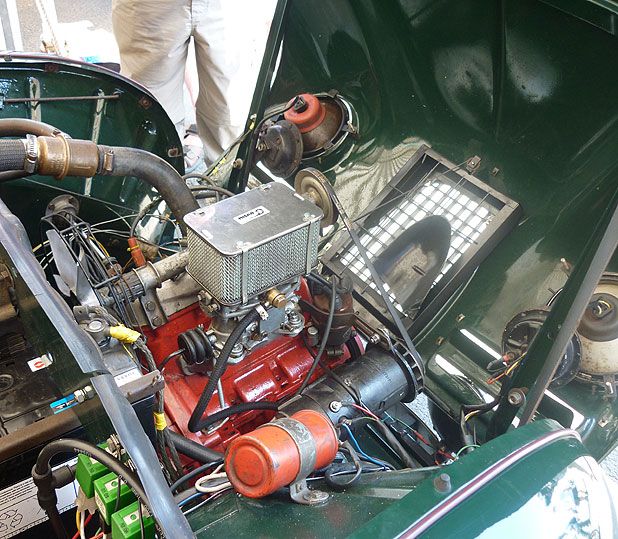

They duly arrived at Le Mans in a car which, apart from the experimental SAH exhaust, was a standard GT750 model. Dismayed that their car was the same colour as the Swedish entry, they resprayed it in British Racing Green on the spot. For them the race was not a success; they retired after four hours with a holed piston. The Swedish car, however, finished 12th out of 13 finishers and averaged 81mph.

Half a century on, the Le Mans Classic is a fabulous event. To see and hear a sea of authentic, period racing machinery driven in anger, divided into six age ranges each with three races over the 24 hours, is breathtaking. So is the gathering of enthusiasts' classic cars in and around the circuit, making it surely the biggest classic car show in Europe and maybe the world. It's an ambition for many a historic racing enthusiast to enter a suitable car in this biennial festival of wonderfulness, and two teams of Saab evangelists – that's the best word to describe the intensity of their enthusiasm – have been dreaming of doing exactly that with a 93.

Two years ago, a Swedish team led by Bo Lindman with an engine from two-stroke racing guru Niklas Enander entered a perfect replica of Swedish car number 44. They won their class and the Index of Performance for the 1957-1961 category, and joy was unbounded. And this year the three Chrises, Partington, Parkes and Nutt, got the entry for a British replica of car 43 to make real the dream that Chris Partington has had for years.

Now, three men all called Christopher could be confusing, so they have gained nicknames. Chris Partington, the mechanical wizard who knows all there is to know about two-stroke Saabs and who built the racer on his front drive from a sun-baked shell found in California, is called Spanner. Chris Parkes, the publicist and a racer of a Ford Anglia 105E, is Parksie. Chris Nutt, who rallies another Saab two-stroke and has got together a six-Saab team for this year's Roger Albert Clark historic rally, is Nutter. And there's a fourth member: ex-Saab Sweden test and racing driver Ferdinand Gustafson, aka Ferdi.

And I was there to support them, because I drove to Le Mans in my own Saab two-stroke, a 1961 96 in – coincidentally – exactly the same colour scheme as the Swedish racer. Driving something ancient and fragile is much the best way to travel to the LM Classic. It puts you in the perfect mood, enlivened by the bitter-sweet risk of mechanical catastrophe – and elation when you've arrived and it hasn't materialised.

At 13.2mph per 1000rpm in the highest of its three forward gears, my Saab doesn't so much cruise as give its all. But it sat happily at 110km/h – it's a left-hand drive car which I bought in 2001 from a mechanic at the Saab museum at Trollhattan and drove home – and its three-cylinder engine, enlarged to a heady 841cc with 38bhp on tap for the 96, sounded just like a tiny straight-six as France passed under the wheels. Various grand and British sportscars were expiring in the 40-degree heat, bonnets up and radiators empty, but the plucky Saab kept on going with the temperature gauge needle never quite reaching the red. Phew!

This huge heat caused problems for the Saab team in Friday's practice. “It was like driving on icy gravel,” announced Spanner. “The chicane on the Mulsanne Straight nearly finished us off before we’d started.” The extreme track temperature was making the tyre pressures too high and the contact patch too small, so letting some air out restored the Saab's usual benign balance. An incident with a flooded carburettor (it's a rare twin-choke downdraught Solex) scuppered Nutter's practice session, but otherwise things were going well.

Spanner started the race and, indeed, the whole event because this year it was the turn of Plateau Three (1957-61) to take the 4pm send-off. After the Le Mans start with drivers running across the track to their cars, the field heads off at full speed only to re-assemble further round the circuit, before following a course car back to the pit straight for the proper rolling start. “By then we were in any old order,” said Spanner, “and we never quite got back into the practice order. There may have been some shuffling but we ended up much further up. Still, it all sorted itself out after half a lap.”

Which means the Saab was running where it was expected to run, pretty much at the back of the field. But it sounded marvellous as it howled past the pits, its two-stroke scream rending the air with an explosiveness a little out of proportion to the visible motion, cheers breaking out through the crowd as they willed the valiant underdog to greater things.

Flat-out, it would be reaching 100mph as the 748cc three-pot unleashed its full 65bhp, while a gallon of petrol, infused with a four per cent dose of oil, would be lasting about 20 miles. However, there has to be a one-and-a-half-minute pit stop within a specific time band in the middle of the 45-minute race, which is when you change drivers if you want to. Spanner duly swapped with Nutter who, having missed out on practice, was now venturing onto the Le Mans circuit for the first time.

He brought the Saab back in one piece, keeping some mechanical health in reserve. Exhaust temperatures can get very high in a two-stroke, enough to melt pistons, so the Saab had a gauge for each port. “Spanner said it shouldn't go above 1200deg C,” said Nutter, “but I only got it to 1100 degrees.”

Parksie did the night section. “He really got in the groove,” said Spanner, “and we were up to second in the Index of Performance. But then we blew it in the final race, with Ferdi driving. We brought him in too early and got a two-lap penalty which knocked us back to fifth. We might have won it if we'd got that little bit right. What we really needed was a team manager. We hadn't thought of that.”

But the team had a great time, and the car held up well. The brakes were vibrating badly by the end, the starter had stopped working and the dynamo had stopped charging, but the engine held together and the spare one stayed unused. “The suspension is too soft,” reckoned Spanner, “and the engine could do with a little more grunt, but it was a privilege to be here. And to be passed on the Mulsanne by cars like Lister-Jaguars gives you the best seat in the house.”

Might we see both replica 93s together at the 2012 Le Mans Classic? That, I thought as my Saab and I ring-ding-dinged back to the chateau that was our weekend base, would be a wonderful sight. And sound.

Text: John Simister

Photos: John Simister / Classic Driver

ClassicInside - The Classic Driver Newsletter

Free Subscription!