With the coachbuilding era all but a distant memory, the in-house styling department of Rolls-Royce and Bentley was relishing its heightened importance in the early 1970s. However, Rolls-Royce chose to appoint Pininfarina to design the Camargue: the manufacturer's first (and last) project to be executed entirely by a third party.

Crewe buys an Italian suit

Unlike Mulliner Park Ward et al, Pininfarina had diversified sufficiently to overcome the death of coachbuilding, offering its consultancy services (and just as importantly, the use of its name) to established manufacturers. Yet the house style Pininfarina bestowed on the Camargue caused panic among Crewe’s top brass when the similarly proportioned Fiat 130 Coupé was unveiled ahead of the Rolls’ imminent launch. An emergency side-by-side evaluation was held and the similarity deemed acceptable. In the words of Rolls-Royce designer Graham Hull, “Although the two vehicles were clearly related, it wasn’t a case of two women wearing the same dress at a social function.”

Pininfarina's Camargue was deemed ill-postured by the in-house design team

As a result, it was green-lighted for production – but the internal design team was far from impressed, their toes perhaps a little sore from their encounter with an Italian leather boot in full stride. The consensus was that the Camargue was ill-postured, with the body overhanging the wheels and sloping down towards the rear, the latter giving the (incorrect) impression that the self-levelling suspension wasn’t up to the job. With little opportunity for body alteration, the in-house team settled for adding wing-witness markers to help the driver place the lengthy bonnet during low-speed manoeuvres. Some years later, the team was given an audience with Sergio himself to describe how the design might be ‘improved’ – Mr Pininfarina’s final response, despite admitting there was room for improvement, was: “I would travel through the rain and fog to be with my child.”

What might have been

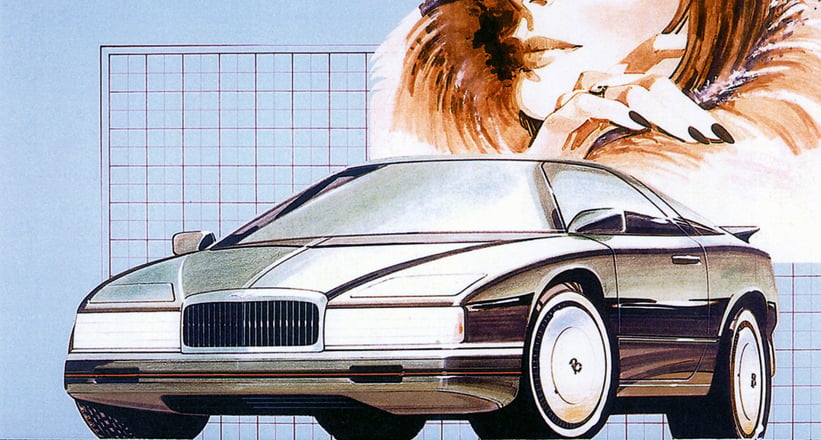

Luckily, the British designers were of the ‘dust yourself off’ mould, an attitude that was further hardened over the coming decades by investing many hours into eventually aborted projects. Perhaps the most interesting are those that never even made it to prototype stage: a Rolls-Royce sports saloon considered in the mid-70s as an aerodyne alternative to the boxy Lagonda saloon; a sporty two-door Bentley explored in the mid-80s (seen above right); and a mid-engined, two-seater Bentley supercar in the mid-90s. The latter, which its designer described as “sanitised Le Mans car meets Ferrari Testarossa,” grew into the Hunaudières concept once VW took charge – and it in turn developed into the Bugatti Veyron.

The BMW-based Bentley

A few years before the mid-engined proposal, the Crewe design team had begun working on another new-ground Bentley – this time a smaller model, roughly based on the package of a BMW 5 Series. The stylists soon found that the traditional, round-headlight front end was not one that liked to be scaled down – so the smallest-ever Bentley coupé was given a radical new face, which incorporated bold headlights and a shorter version of the trademark grille. Despite being well received at the 1994 Geneva Show and having an agreement for a collaborative production run with BMW in place, the few Javas eventually built (coupés, convertibles and estates) were those commissioned by a well-known collector. But although the partnership with BMW failed on this occasion, it gave the Germans a taste for an established British image – and we all know how that turned out.

Photos: Graham Hull / Rolls-Royce Motors / Bentley Motors