Paul Bouvot. For some of you, this name won’t mean a great deal. But he might be the most important man of Rétromobile 2015, for several reasons. First, as head of the Peugeot design department in the 1960s, he was responsible for the popular Peugeot 204, which will celebrate its 50th anniversary this year – more specifically, during the Parisian classic car week. He’s also one of the best-known automotive artists and three of his paintings will be offered at the Artcurial auction. But the most important reason is his link to the star of the show: the ex-Alain Delon ‘barn-find’ Ferrari 250 California Spider. He bought the car directly from Alain Delon and, at the time, his son Marc was smart enough to keep all the documents of the sale. We recently met up with Marc to find out a bit more about Paul Bouvot, and how the special car arrived in his life.

What was Paul Bouvot’s earliest automotive experience?

Paul was born into a motoring cooking pot, and he had his first pedal car by the age of two. His early childhood was spent in the French Jura, where he was raised hearing the melody of his uncles’ Bugattis, and the violin music of his father Auguste, who was a Citroën dealer. When he was still a child, he and his parents moved to Dijon and lived very close to the Terrot company, which produced the famous motorcycles. Soon, he was spending more time in the workshop than at school.

And then he began to work at Terrot?

No, he met Edmond Padovani, who was technical manager and Works racer for Terrot at the time. Seeing how motivated Paul Bouvot was, Padovani decided to entrust him to take the racing handlebars for a season, although he didn’t have much success…

What happened then?

He began to work at Labourier, a tractor manufacturer located in the French Jura mountains. But then came WWII, and he entered The Resistance. He was captured and deported to Dachau where, by chance, he wasn’t killed. At the end of the war, he discovered American culture and went back to Labourier, where he worked as project manager on its new tractor. He took his inspiration from what was being made in the U.S. at the time and created the first European tractor with an integrated chassis: the Labourier LD15.

So how did he begin working with cars?

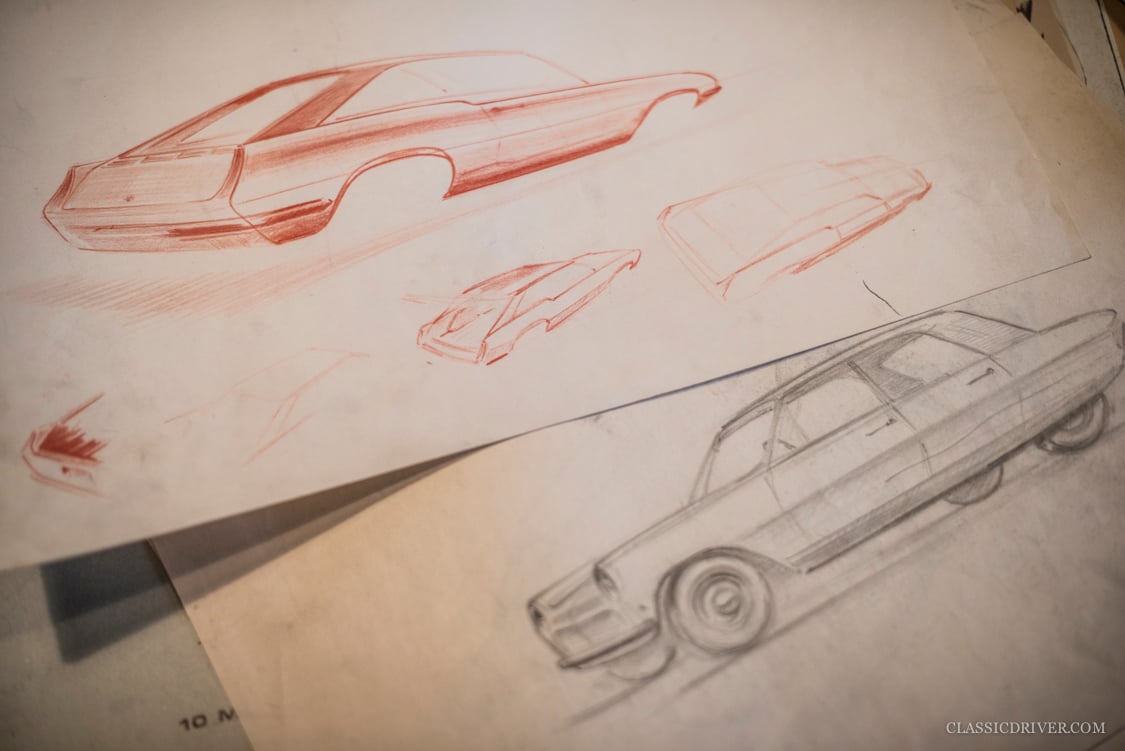

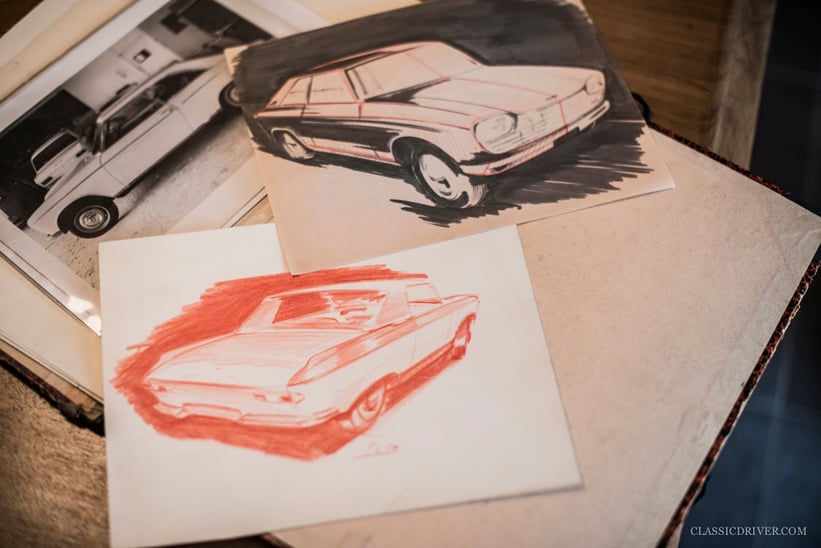

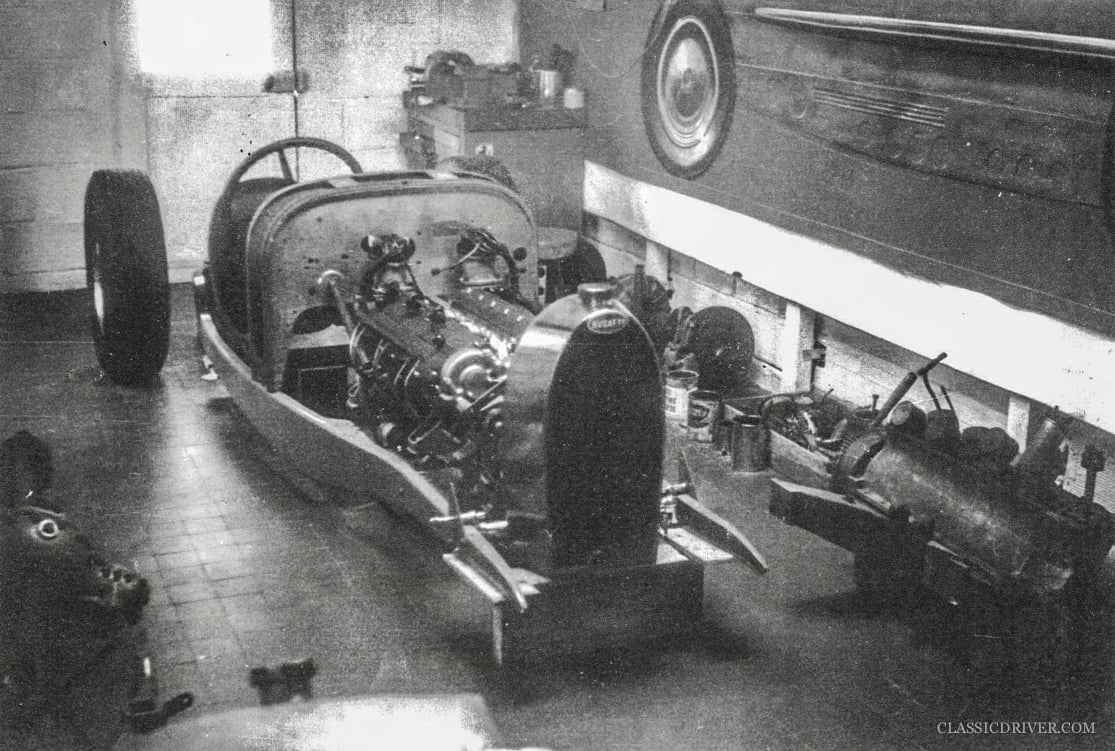

In his own words, he was a ‘paid slave’ at Terrot and Labourier… and therefore didn’t have the money to buy his dream car, which was a Bugatti Type 51. However, such was his passion, he decided to build his own car, looking at what was being done at the best brands, such as Ferrari. The result was his own barchetta: a homemade tubular chassis, a steel hand-formed body and a little Simca engine. It took him four years to finish the car and, by the time it was done, he had some new ideas and had to sell the car to finance one of them, a berlinetta. That car has completely disappeared, but the barchetta is now literally ‘back home’... in my living room!

Was this second car an important step for him?

Indeed, this was the car that kick-started his career. He used it as his daily driver and, one day, he left it parked in a village and came back to a note on the windscreen: “I’m Peugeot’s head of design. I want to meet you.” At first, he couldn’t believe it.

And so he began to work for Peugeot?

Yes, they met in Paris soon afterwards and he was hired by Peugeot. At the beginning, his role was to manage the relationship between Peugeot’s and Pininfarina’s designers, as they were collaborating at the time. As his financial situation improved, he bought his first old car: a Bugatti Type 57. By the end of the 50s, he had been promoted to head of Peugeot design, and a major projects manager. He built up a good friendship with Sergio Pininfarina, and each time he went to Italy to visit him to view the latest design proposals, Sergio took him out in the latest Ferrari models. He met all the legendary Italians of this era, even Enzo himself.

Was that when he started buying Ferraris?

Not straight away. Thanks to his promotion, he earned more money, so he bought his second Bugatti: a Type 35. This is how he met the famous band of enthusiasts: Novo, Catanéo, Ampoullier, Mortarini, and a bit later Jess Pourret. And while he was driving the Bugattis that he had always loved, his passion for Ferrari was growing…

In the 60s, Paul Bouvot became an important figure in the world of car design, correct?

What type of collector was Paul Bouvot?

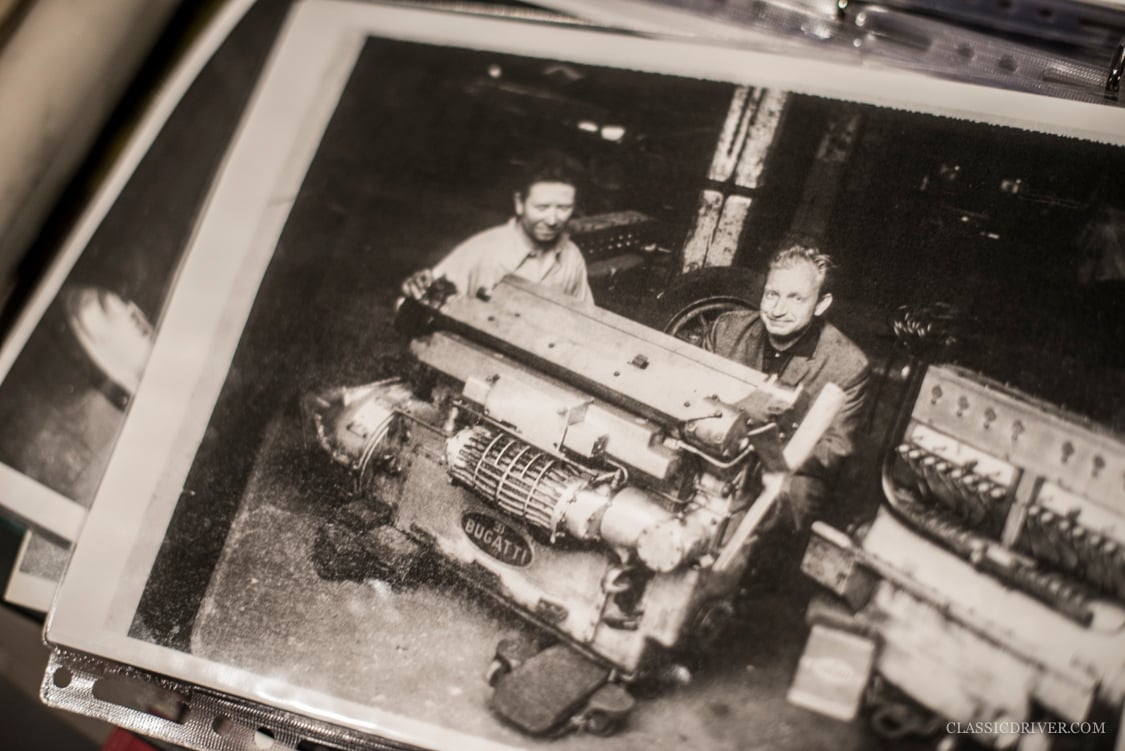

He wasn’t a collector in the traditional sense. He was more of a mechanic, a technician, so he always dismantled every car he bought in order to modify it, regardless of how special it was. With his friend Henri Novo, he had the crazy idea of installing the V12 from his 212 Inter into a Bugatti Type 35 chassis, purely to make his friends laugh. This was surely the most incredible hybrid of all time: the Ferratti.

How did he start with the Ferraris?

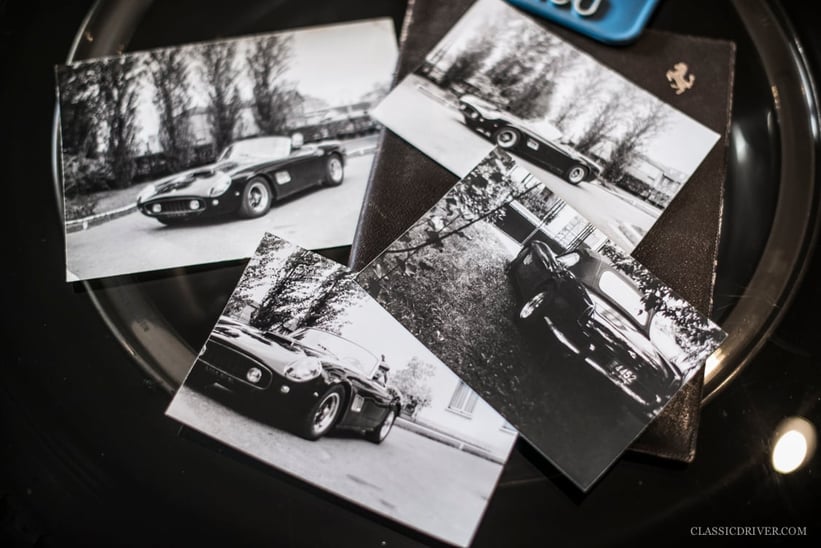

His first Ferrari was a 212 Inter that he immediately dismantled in order to shorten it to 2.4m, and drive it as a bare chassis through Paris – with the headlights still attached to make sure it was road legal. My ears are still ringing from the scream of the V12, mixed with the sound of Jess Pourret’s berlinetta that was in front of us, when we journeyed from Colombes to the ‘L’Orée du Bois’ restaurant in the Bois de Boulogne. He then sold the 212 Inter, which has otherwise largely disappeared from my memory and my archives… and bought an accident-damaged PF Coupé as a restoration project. Sergio Pininfarina and Enzo Ferrari helped him to find all the parts to restore it, and he sold it. Next was another Coupé PF, this time in perfect condition. But he found it too bourgeois, too heavy, too wheezy, and so he sold this one, too. Then came the California Spider, chassis #2935…

Tell us more about this car, the star of Artcurial’s 2015 Rétromobile auction…

He bought it directly from Alain Delon through Michel Urman Automobiles in Paris, as is stated on the documents I kept. Paul was never really interested in keeping old documents, archives, etc. It was more my thing. For each car, I kept as many things as I could – every photo, and all the paperwork, such as insurance certificates carrying Alain Delon’s name, the sale documents, and the Monaco licence plates we see in every picture of the California with Alain Delon at the wheel. All these souvenirs stayed in a shoebox for decades, as everybody thought the car had disappeared. I remember him telling me a story about it: he discovered that it was very hot in the car when he was driving with the roof up. So, as he did with every car, he modified it, installing a large zip-up rear window. He kept it for just under a year, covering more than 2,500km behind the wheel.

Was it his last car?

Not at all. He sold the California to buy another Cal’ Spider through Jess Pourret: chassis #2175, the ex-Roger Vadim car, which had around 40bhp more. He then sold this California to buy a 275 GTB/2, sold one year later to buy a Lamborghini Miura. He kept this for two years, and sold it after some unfortunate experiences: once, Paul let a friend of his, a Ferrari fanatic, test drive the car. Carrying plenty of speed coming into an awkward left-hand curve, his friend lifted his foot from the gas pedal – but the car continued accelerating. As an experienced Ferrari driver, he quickly reached for the ignition key to kill the engine… a key that he never found. Luckily, Paul recognised the dire situation, and killed the engine himself, knowing the ignition was on the centre tunnel and not on the steering column. They managed to avoid an accident. A few weeks after this, at full speed on the highway with Paul behind the wheel, the car did a double pirouette. Somehow, he didn’t hit anything – but that was enough for him: he sold the Miura, and bought a bicycle.

Which car left him with the best memory?

Definitely his uncles’ Bugattis, when he was a child.

Did Paul Bouvot own many cars at the same time, or did he only buy cars one after the other?

No, he never had two cars at the same time, probably for financial reasons. That was a big regret of his: having to sell some of his cars to finance others. That’s why he always told me: “Marc, always keep your cars.”

What influenced his choices? The aesthetics, the engineering, or a mixture of both?

The engine and its melody. He often said: “a car is an engine above all.”

What’s your view of his professional career as a designer?

His professional career was permanent joy and permanent suffering. Economic necessities led the “axe commission” to destroy his most audacious projects.

What did your father do after his career in automotive design?

He was succeeded by Gerard Welter in 1980, but remained a consultant for Peugeot for several years afterwards. He spent most of his time focusing on his other passion: painting. He had four main themes: cars, engines, trains and ladies. Just like when he worked as a designer, he painted day and night.

What’s your view on his pictorial work?

His work appeals to real connoisseurs; I’m very proud of what he accomplished in this field. He painted about 150 masterpieces, some of which were unfinished. My friend and neighbour Lionel and I are currently referencing them all, taking into account the inventory put together by Christian Huet in 2000. Later this year, we’ll put this work on the internet, and offer some of the paintings for sale. In the meantime, I’m selling three pieces during the Artcurial Motorcars automobilia sale at Rétromobile.

When you speak about your father, you refer to him as ‘Paul Bouvot’ and never ‘my father’, or ‘dad’. Why?

Despite his charisma, his culture, his ability to listen, his very human dimension and his talent – to me, he has always been more of a friend and a good advisor than a father. He wasn’t a born father in the traditional sense, but I never missed it, as he was such an exceptional person.

What type of collector are you?

I’m not a collector. Paul, and my engineering studies, gave me a love for mechanics. On top of this, just add a zest of memories, a pinch of nostalgia – and in my back yard, you’ll find a Peugeot 204 Coupé, a Labourier LD15 tractor, the Paul Bouvot barquette, and a few Ferraris that I’ll never sell, just as Paul instructed me.

Is there a car that your father always wanted to have, but couldn’t afford?

A Bugatti Type 51. But most of all, Paul was realistic, and was a quite simple man. After he survived his deportation to Dachau, he was content with everything that life brought him. He passed this philosophy on to me, and I think that when the hammer falls for #2935 at the Artcurial Motorcars sale, I’ll feel a real sense of joy for the new owner.

Photos: Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2015